Why Did IBM Reopen Its Defined Benefit Plan? Will Others Follow? – Center for Retirement Research

[ad_1]

The brief’s key findings are:

- IBM has reopened its defined benefit plan to use the plan’s surplus – rather than corporate cash – to fund retirement contributions.

- This shift has been fueled by a more favorable regulatory environment and the improved funded status of defined benefit plans.

- While using “trapped surpluses” helps the firm, workers may well come out behind unless the gains are shared.

- Interestingly, the analysis finds that only a handful of other large companies are likely candidates to follow IBM’s lead.

- Thus, the move should be viewed as a financial maneuver, not a meaningful change in the provision of retirement income.

Introduction

Enthusiasm seems to be growing to reopen – or at least to stop closing and freezing – defined benefit retirement plans. The impetus comes from a more benign regulatory environment and the improved funded status of these plans, even before the recent rise in interest rates. Reopening plans allows employers to use surplus assets, which if reverted to the sponsor would be subject to a 50-percent excise tax in addition to the employer income tax. The most dramatic manifestation of this enthusiasm for reopening plans has been IBM’s announcement to shift its 401(k) match to an automatic contribution to the cash balance component of its previously frozen defined benefit plan.

This brief lays out the implications of IBM’s shift for the company and its employees, and speculates about which companies might follow IBM’s lead. Specifically, the discussion proceeds as follows. The first section describes the changing regulatory environment and financial status of single-employer defined benefit plans. The second section provides the details of IBM’s startling move and its implications for both employers and employees. The third section identifies large overfunded plans that could follow IBM’s lead.

The final section concludes with two points. First, plan sponsors clearly gain by putting the “trapped” surpluses to use, but, without some sharing of the gains, employees may well come out behind. Second, among major companies, only a handful are likely candidates to reopen their defined benefit plans. The nation’s largest banks lead the list: Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase are particularly well positioned, but Citigroup is also a possibility. Two non-financial firms – Honeywell International and Deere & Co. – are also potential candidates.

Regulatory and Financial Developments

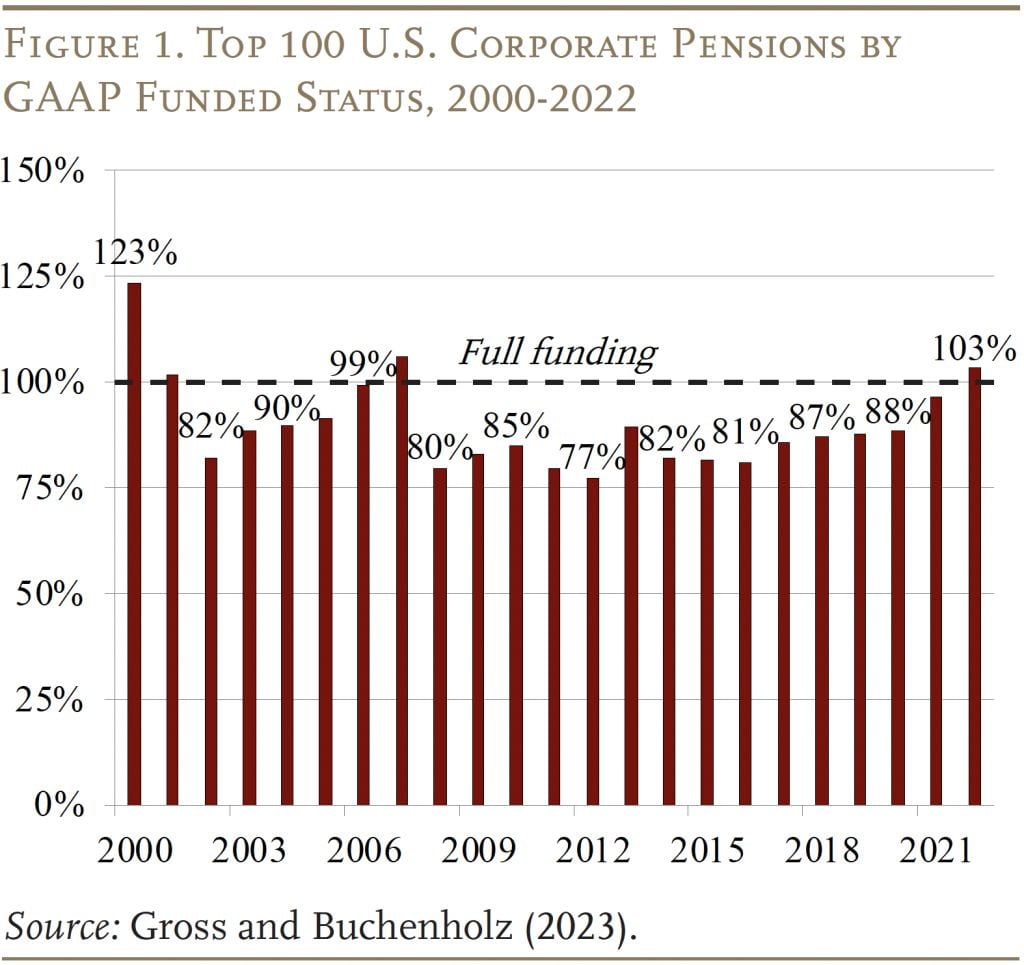

The shift from defined benefit pensions to 401(k) plans has been underway since 1981, but during the 1980s and 1990s this trend reflected a surge in 401(k)s – not the closing of defined benefit plans. In fact, the 1990s were a great time to sponsor a defined benefit plan. Growing asset values allowed sponsors to make little or no cash contributions to their pension funds. By the turn of the century, pension assets amounted to 123 percent of liabilities (see Figure 1).

The scene changed dramatically in 2000 when the tech bubble burst and interest rates tumbled, highlighting the mismatch between assets and liabilities. In response, Congress tightened funding rules in the 2006 Pension Protection Act. For single-employer pension plans, it first set the period for amortizing all unfunded liabilities at 7 years. Second, it specified three interest rates to be used for discounting promised benefits. The rates, called segment rates, depend on when the benefits are expected to be paid – in less than 5 years, 5-20 years, and more than 20 years. The segment rates are corporate bond yields averaged over the preceding 24 months.

At the same time that Congress tightened funding standards, the Financial Accounting Standards Board changed the reporting requirements, forcing corporations to treat net pension liabilities as debt on their balance sheet.

Shortly after the tightening of funding requirements and the adoption of stricter accounting rules, the stock market and the economy collapsed in the Global Financial Crisis (2007-2009). With the new provisions, the drop in funded status imposed real costs on sponsoring corporations – their income and balance sheets took a hit, and they faced a sharp increase in required pension contributions.

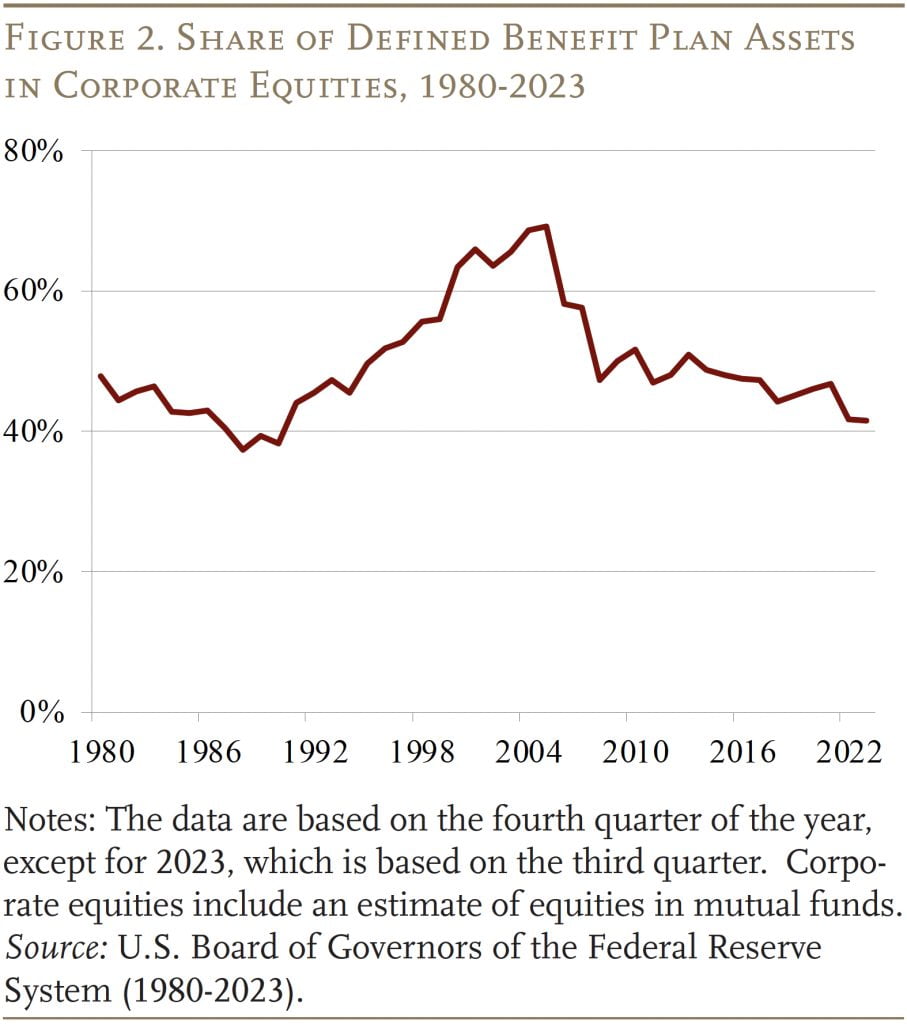

In response, corporate sponsors did two things. First, they changed their plans’ asset mix, which included moving away from equities (see Figure 2) and purchasing bonds that matured as benefit liabilities were projected to fall due (liability-driven investment). At the same time, they began closing and freezing their defined benefit plans in favor of 401(k)s. Many defined benefit plan sponsors put themselves on a path to eventually get out of the business altogether.

In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, two developments made single-employer defined benefit plans more attractive. First, their finances improved. The change in asset allocation made them much less vulnerable to market swings, and a rising stock market led to higher asset values. At the same time, the closing and/or freezing of plans slowed the growth in liabilities. As a result, the ratio of assets to liabilities increased from a low of 77 percent in 2012 to 96 percent in 2021. Of course, the spike in interest rates in 2022 – despite poor market returns – boosted funding levels even further.

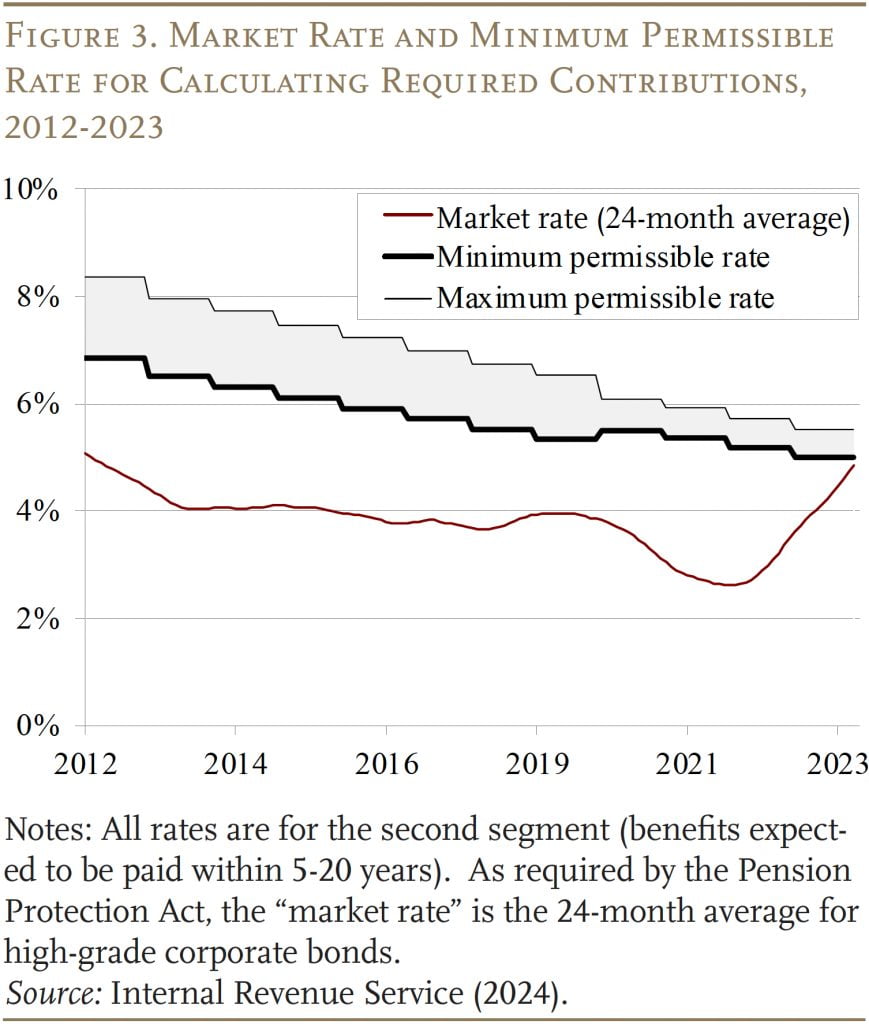

Second, Congress provided funding relief. The first crucial piece of legislation was the 2012 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, which permitted the market rate established by the 2006 Pension Protection Act to be averaged over the prior 25 years – a period when rates had been significantly higher. It also established a corridor that set the minimum and maximum rates at 90 percent and 110 percent of the average, respectively.

The 2012 legislation envisioned the corridor widening over time, which – with market rates significantly below the corridor – would have decreased the discount rate and increased liabilities and minimum required contributions. But additional iterations of funding relief prevented this widening from occurring. As a result, the rate used to calculate liabilities for funding purposes has been about 200 basis points higher than the “market rate” specified in the Pension Protection Act (see Figure 3).

For single-employer defined benefit plans, the second and most dramatic pieces of funding relief were included in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. First, it set a floor of 5 percent on the 25-year average and narrowed the corridor around the average to the range of 95 percent to 105 percent. This change comes just as the 25-year average was moving away from historically high rates, which would have eliminated the gap between the minimum permissible rate and the “market rate.” The legislation also permanently increased the amortization period from 7 years to 15 years, which increases the time for underfunded plans to reach full funding.

A series of three influential articles from JPMorgan Asset Management argue that the improved financial condition of defined benefit plans – better funded and less risky – and the funding relief have “severed the link” between movements in market interest rates and required pension contributions. Since the fear of large required contributions was a major factor that drove employers away from defined benefit plans, the elimination of contribution risk should lead sponsors to rethink possible ways to use the “trapped assets” in their defined benefit plans. It seems like IBM was listening to this advice.

What IBM Did and Why

Starting in January 2024, IBM ended its 5-percent matching contribution and 1-percent automatic contribution to employees’ 401(k) accounts in favor of an automatic 5-percent contribution to a “Retirement Benefit Account” for each employee. The Retirement Benefit Account is the employee’s “notional” account in the cash balance component of the company’s defined benefit plan. IBM had closed its defined benefit plan to new participants in 2005 and “frozen” benefits – that is, ended new accruals – for existing participants in 2008.

Cash balance plans are defined benefit plans that retain notional individual accounts until the account is paid out to the individual. Like traditional defined benefit plans, the employer makes the contributions and bears the investment risk, while the plan fiduciaries manage the investments. In addition, the plan credits the employee’s account with notional earnings, usually as interest based on the current yield on pre-selected Treasury securities. Employees receive regular statements and typically can withdraw the balance as a lump sum when they retire or terminate employment. Unlike 401(k) plans, however, cash balance plans are required to offer employees the ability to receive their benefits in the form of an annuity for the employee’s life or for the lifetimes of the employee and the employee’s surviving spouse.

Historically, IBM had automatically enrolled new employees in its 401(k) plan at 5 percent of salary after 30 days, unless the employee opted out. After one year, employees then became eligible for IBM’s 5-percent matching contribution and 1-percent automatic employer contribution. Under the new arrangement, employees receive a monthly credit of 5 percent of pay into their Retirement Benefit Account, with the option to save additional amounts through the company’s traditional or Roth 401(k) plans. To compensate for the loss of the company’s previous 1-percent automatic employer contribution, IBM increased salaries by 1 percent effective January 1, 2024.

The guaranteed rate of notional earnings for IBM’s new Retirement Benefit Accounts are as follows:

- first 3 years: 6 percent interest;

- 2027-2033: yield on 10-year Treasury, with a floor of 3 percent; and

- 2034 and beyond: yield on 10-year Treasury.

What Does This Shift Mean for the Company?

The most significant benefit of the shift is that it allows IBM to fund retirement contributions with the surplus in its overfunded defined benefit plan rather than with corporate cash contributed to its 401(k) plan. According to its annual report, IBM held a surplus of $5 billion in its defined benefit plan, while it paid out $530 million annually in matching and automatic 1-percent contributions to the 401(k). Faced with no funding requirements for its over-funded defined benefit plan, IBM can use the $5 billion surplus in the plan to pay for the 5-percent monthly credits provided to employees’ notional individual accounts for at least the next 10 years – improving its cash flow statement by about $500 million each year. Eventually, IBM will have to make contributions to the plan out of company money, but good investment performance could help reduce the annual burden.

The drawbacks are modest compared to the gain. First, regular actuarial analyses and annual premiums to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation make defined benefit plans more expensive to operate than 401(k)s. Second, the IBM plan will have to provide the interest credits to participants’ notional accounts, which, as noted, will amount to 6 percent in the short run. These payments are not necessarily linked to the investment performance of the assets, which will require some hedging effort on the part of IBM. Third, the reduction in the plan’s surplus to fund the monthly pay credits will show up as a negative adjustment in the company’s financial statements. Eventually, IBM will have to make some funding contributions, but the payment schedule will be much more flexible than the annual contributions to the 401(k) plan. Alternatively, at that point, the company could just re-freeze the DB plan and revert to the earlier pattern of making cash contributions to the 401(k) plan. In either case, the company clearly comes out ahead.

What Does This Shift Mean for Employees?

While IBM clearly gains from this maneuver, its employees may well lose. On the positive side, employees not participating in the current 401(k) or not maxing out the employer match will definitely gain, but the gains here would be very small since 97 percent of workers at IBM participate in the 401(k). Similarly, the ability to receive lifetime benefits – provided at very low cost – could alleviate some of the challenges associated with withdrawing 401(k) balances and purchasing an annuity. But the gains here depend on how many participants opt for the lifetime benefit as opposed to the lump sum, and also – as in the case of an annuity purchased with 401(k) dollars – the value of lifetime income depends crucially on what happens on the inflation front. In short, the potential gains for employees are modest.

In contrast, the potential losses for employees are meaningful. First, if employees do not adjust the asset composition of their 401(k) contributions, they will have too much of their assets in fixed-income investments. After the higher initial guarantee, IBM will provide credits equal to the yield on Treasuries. If the company’s 5-percent contribution had gone into the 401(k) instead, it would earn the return on a mix of stocks and bonds – presumably higher. In addition, without a match, employees may well cut back on their 401(k) saving and end up putting less aside for retirement. On balance, employees are likely to come out behind.

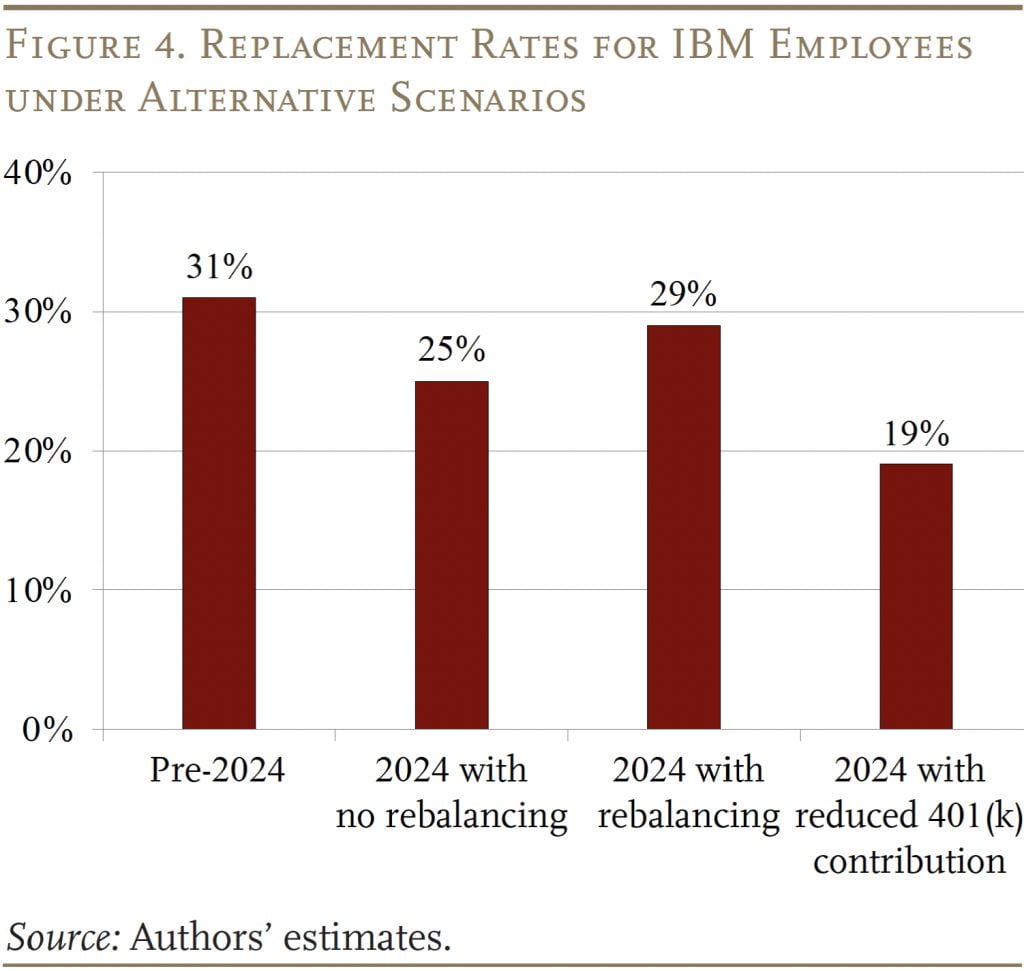

A simple simulation can provide some sense of how the employee’s behavioral response can affect the outcome. The analysis focuses on a new employee who is age 30 in 2024 and retires at 65. Without IBM’s switch, this employee contributing 5 percent to the 401(k) plan and receiving the 5-percent matching contribution – assuming a portfolio of 60-percent equities and 40-percent bonds – would have a replacement rate of 31 percent from the IBM plan at retirement. If the employee now saves 5 percent in the 401(k) invested 60/40 in equities and bonds and 5 percent in a cash balance plan with IBM’s design (the 10-year Treasury except for guaranteed returns in the early years), the replacement rate drops to 25 percent. If the employee rebalances and puts all his 401(k) assets in equities, the replacement rate recovers, but not all the way back because the ratio across both plans is 50/50 not 60/40. Finally, the employee can decide to save less in the absence of an employer match. If the employee cuts the 401(k) contribution to 3 percent, and does not rebalance, the replacement rate drops to 19 percent. The important point is that all the potential outcomes for the employee are lower than under IBM’s previous arrangement (see Figure 4).

Will Others Follow?

Will other corporate sponsors follow suit and reopen their defined benefit plan? As discussed, IBM’s gain comes from using the surplus in its overfunded defined benefit plan to improve its cash flow by reducing its ongoing retirement contribution costs. Accordingly, a potential follower should have: 1) a large defined benefit surplus that can be put to use; and 2) large 401(k) contributions that, once saved or reduced, can significantly improve the company’s cash flow. In addition, an existing cash balance component in the current closed/frozen plan may make the transition easier, and a plan that covers non-unionized employees would avoid the need for negotiations.

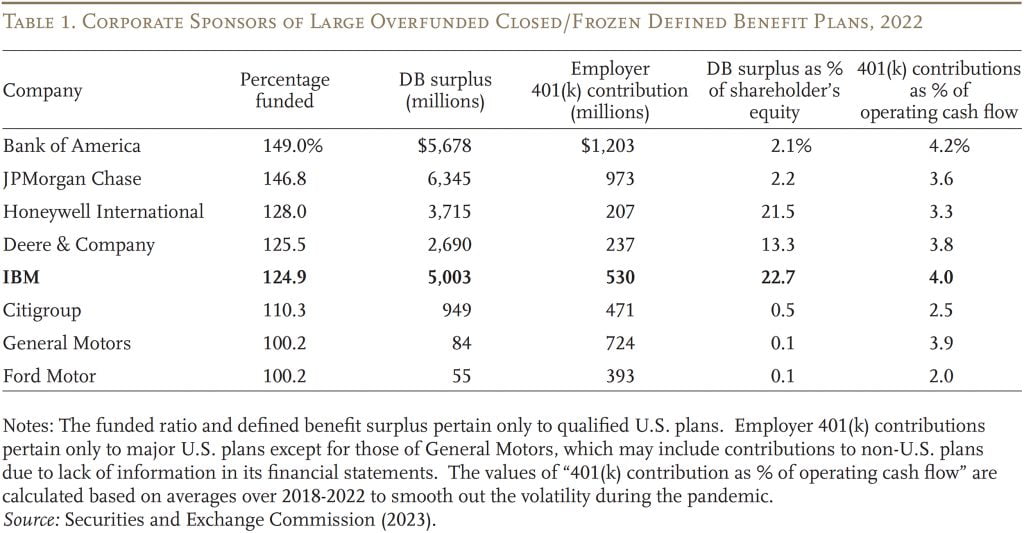

The analysis started by looking at the 45 U.S. companies with defined benefit obligations of more than $10 billion. Narrowing the focus to closed/frozen plans with a funded ratio over 100 percent resulted in eight companies. These companies, ordered by their funded ratios, are shown in Table 1. The table also includes the surplus in the company’s defined benefit plan, contributions to the company’s 401(k) plan, and two measures that might provide an incentive to consider IBM’s approach – the defined benefit surplus relative to shareholders’ equity and 401(k) contributions’ relative to annual cash flow. Not surprisingly, IBM ranks high on both incentive measures. All companies except Ford have a major cash balance component in their plans.

On the top of the list are the nation’s two largest banks – Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase. The sheer dollar amount of their pension surpluses may trigger serious consideration of potential alternative uses. Also, these companies made large 401(k) contributions both in dollar amount ($1.2 billion and $1 billion, respectively) and as a share of their annual cash flow (4.2 percent and 3.6 percent, respectively). These numbers imply that the potential gains from reopening their defined benefit plans could be even greater than IBM’s. Citigroup, the fourth largest U.S. bank, is also on the list with a funded ratio of 110 percent, although its defined benefit surplus and 401(k) contributions are much lower than the top two. As few financial sector employees are unionized, these banks would have great discretion in setting plan provisions if they decided to reopen the cash balance component of their defined benefit plans.

Honeywell International and Deere & Co., which are third and fourth on the list, face a situation similar to IBM’s in terms of the relative sizes of their surpluses and 401(k) costs. Deere & Co. may not take further actions anytime soon as it just closed its defined benefit plan for salaried employees to new hires in January 2023 and greatly enhanced its 401(k) matching rate. However, down the road, a rapid increase in 401(k) costs could trigger a reconsideration of the defined benefit option.

General Motors and Ford seem unlikely to follow IBM in reopening their barely fully funded defined benefit plans. Restoring their defined benefit plans was actually on the list of demands of the United Auto Workers during the strike in 2023, and the automakers rejected it. Instead, the auto companies agreed to increase their 401(k) contributions from 6.4 percent to 10 percent of pay with no required employee contributions. Although General Motors and Ford are likely to see increased 401(k) contributions in coming years, they just do not have the defined benefit surplus needed to adopt IBM’s approach.

Overall, the big banks – Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and maybe Citigroup – and two nonfinancial companies – Honeywell International and Deere & Co – are the most likely candidates to reopen their defined benefit plans.

Conclusion

IBM’s shift to reopen its defined benefit plan for retirement benefits is a significant development in the world of pensions. It is a financial maneuver, however, that allows IBM to fund retirement contributions with the surplus in its overfunded defined benefit plan rather than corporate cash; it is not a meaningful change in how the private sector provides retirement income. The move has been fueled by a more favorable regulatory environment and the improved funded status of these plans. While tapping “trapped “surpluses” benefits the company, employees face less flexibility in their investment options and likely lower replacement rates. Only a handful of other large companies are positioned to follow IBM’s lead. The nation’s largest banks head the list: Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase are particularly well positioned, but Citigroup is also a possibility. Two non-financial firms – Honeywell International and Deere & Co. – are also potential candidates.

References

Congressional Budget Office. 2023. The 2023 Long-Term Budget Outlook. Washington, DC.

Gross, Jared and Mike Buchenholz. 2023. “Pension Defrost: Is It Time to Reopen DB Pension Plans—or at Least Stop Closing and Freezing Them?” Report. New York, NY: JPMorgan Asset Management.

Gross, Jared and Michael Buchenholz. 2022. “The Roadmap to Pension Stability.” Report. New York, NY: JPMorgan Asset Management.

Gross, Jared and Michael Buchenholz. 2021. “Rethinking the Pension Plan Endgame: Hibernation, Termination or Stabilization?” Report. New York, NY: JPMorgan Asset Management.

IBM. 2023. “IBM Benefits 2024 IBM U.S. Benefits Guide.” Armonk, NY.

Internal Revenue Service. 2024. “Pension Plan Funding Segments.” Washington, DC.

JPMorgan Asset Management. 2024. “2024 Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions.” 28th Annual Edition. New York, NY.

Munnell, Alicia H., Mauricio Soto, J.P. Aubry and Christopher J. Baum. 2007. “Why Are Companies Freezing Their Pensions?” Working Paper 2007-22. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Securities and Exchange Commission. 2023. Financial Statements filed by various companies. Washington, DC.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Financial Accounts of the United States, 1980-2023. Washington, DC.