Every few months, news breaks of another high-profile rider throwing their leg over a 3D-printed bike. Alex Dowsett, Filippo Ganna, world scratch race champion Will Tidball. The list isn’t exactly endless, but each one makes headlines and increases the sense of mystery. A shroud seems to cover 3D printing, and as manufacturers disclose scant details, excitement builds around a dark and exciting art coming soon to a garage or shed near you.

In truth, it’s not dark, but it can certainly be exciting, and the possibilities it offers all of us are closer at hand than you might imagine. If your instinctive reaction when you first found out that someone printed a bike was along the lines of “How the–?”, then you’ve come to the right place.

A very brief description of how it works: the printer takes the material you feed it – whether that’s a plastic filament or (if you’re very rich) powdered titanium, or some other material – and melts it onto a baseplate, building it up in very fine detail, layer by layer, until the piece is complete. This isn’t like your standard home laser printer chucking out a side of A4 in under 10 seconds, though. Unless you’re 3D printing something very small, it’s an hours-long process.

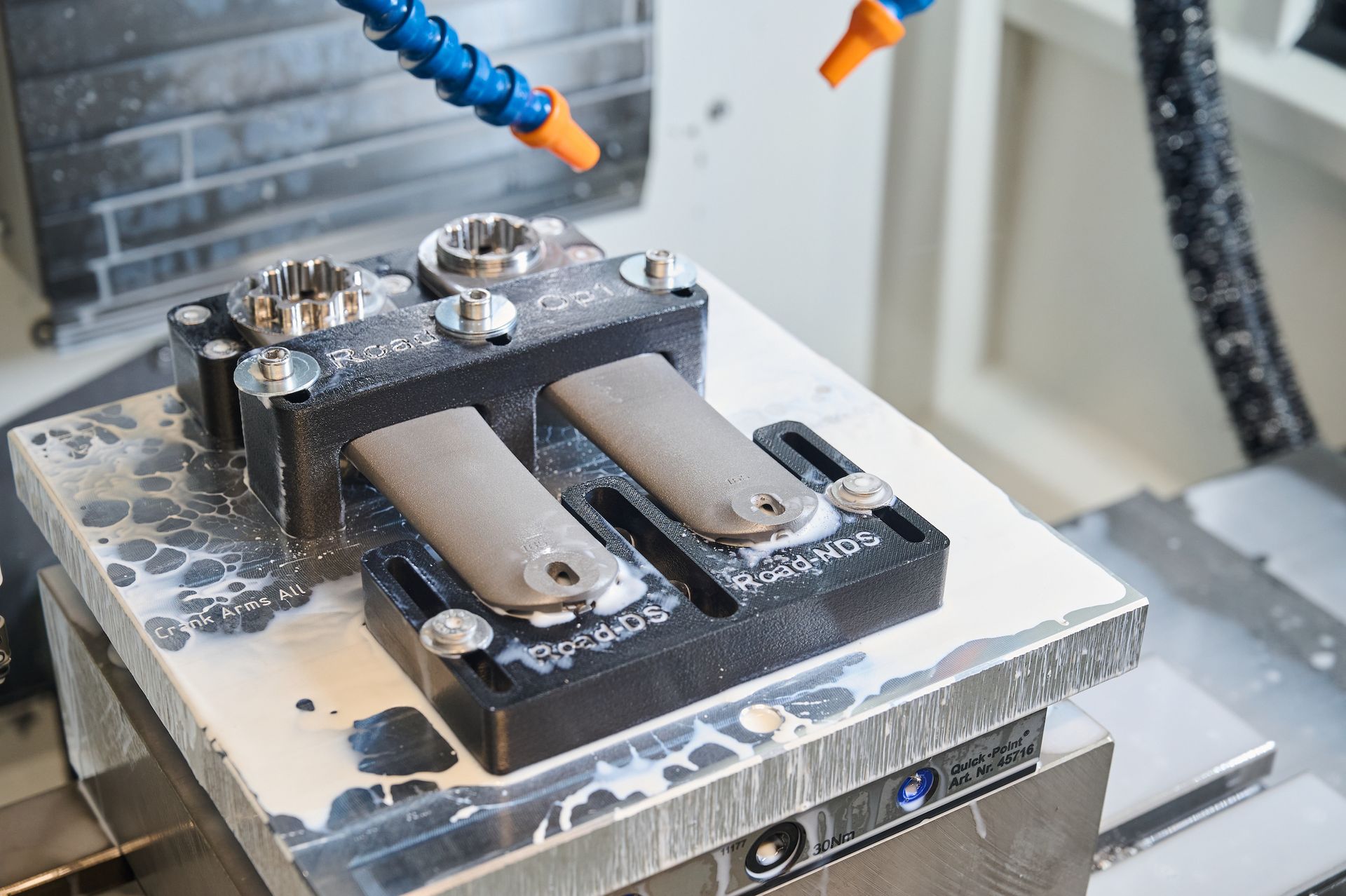

Sitting somewhere among the top branches of cycling’s 3D printing tree is Tom Sturdy. He runs Sturdy Cycles in Frome, Somerset, where creates bikes in titanium, employing the liberal use of 3D printing for everything from chainsets to cockpits, brake levers and even rear triangles. “I started building frames properly about 10 years ago,” Sturdy said. “I was doing steel – conventionally manufactured steel frames, steel tubes either brazed or welded together.”

(Image credit: Future)

A few years ago, he switched to making bikes in titanium, using 3D printing combined with CNC machining in his own workshop, enabling him to become more efficient and work with a material for which customers expect to pay a premium price. Importantly, it also enabled Sturdy to maintain the uniqueness of the bikes he was selling.

While Sturdy has his own CNC machine in his Somerset workshop, the 3D-printed parts aren’t so locally made, at least for the time being. He sends his designs to a supplier in New Zealand, which ships them over. That said, he has used UK suppliers too. “We do everything in-house here with the exception of the metal printing, and that is because of [the cost],” says Sturdy. “You’re talking millions to buy one of those printers and then keeping it running is not a small task either. All of a sudden it becomes a very different business.”

If 3D printing in cycling was restricted to titanium and other expensive metals such as the scalmalloy purportedly used in Ganna’s, Dowsett’s and Tidball’s bikes, it would be far more niche than it is. However, you can go online and buy, for less than £200, a budget 3D printer that will print in various forms of plastic including biodegradeable PLA, derived from cornstarch. Spend northwards towards £1,000 and you’ve got a piece of kit that can turn out pro-level results. The printing plastics are eminently affordable – starting at around £20 a kilo – and it stands to reason you could knock up quite a few 25g bottle cages or cable clamps before running low on a block like that.

Aerodynamics company Aerocoach, which works with top-level teams and riders, uses 3D printing extensively, as director Dr Xavier Disley explains. “It’s an integral part of what we do, for sure,” he says. “We have products that are 3D-printed; we have products that are part 3D-printed, we’ve got 3D printers of various types.” The company also uses 3D printing for prototyping, where the low cost makes it ideal for producing one-off items and making small alterations.

(Image credit: Aerocoach)

“[We use] the PLA stuff for very rough prototyping, getting a feel for something,” says Disley. “We’re making a product at the moment which you could fit in your hands, and it’s just good to get hands-on with something. Because you can look at all the CAD models that you want on the computer, but you never really know.” Disley also prints with resin, which can achieve a higher resolution (accuracy) for prototypes where seeing how things fit to the nearest fraction of a millimetre is required.

When it comes to the end product, 3D printing can be used to create customised pieces without the need for multiple expensive carbon moulds. “Carbon moulding is really expensive,” Disley says. “The tooling costs are nuts. So you have to be really careful about how you incorporate that into your pricing plan, because you’re going to have to pass it on to the consumer at some point.” Disley gives the example of time trial bar extension end-grippers: “The gripper is made out of [3D printed] nylon, so it means we can change the shape of it pretty quickly… We can have loads of different skews. Then we bond that nylon piece into a carbon shaft or a titanium 3D-printed shaft if we want to make it a little bit lighter,” he explains.

When it comes to pieces of tube such as those bar extensions, 3D-printed titanium trumps carbon in that it enables manipulation of the internal walls. A lattice can be introduced, for example, and it’s significantly easier to create different wall thicknesses.

Making a bike frame using the process is far harder – hence the £55,000 price tag on the retail version of Tidball’s machine.

Printing for the peloton

Not surprisingly, Disley’s kit is not the only 3D-printed goodness to find its way into the pro peloton. Sam Rees is a mechanic with German Continental team Maloja Pushbikers. He ended up buying a 3D printer with a view to furnishing the team’s bikes with various trinkets. “I was printing number brackets for the riders, and just carried on,” says Rees, who prints in a plastic called PETG. “I don’t do anything structural; it’s much better to just do plastic and then you don’t have to worry that something might fail. So it’s normally things like number holders, bottom bracket spacers, little things.”

One of Rees’s most recent prints is a checking tool for the UCI’s new brake lever angle regulations. Issued as a template by the UCI itself, the tool enables Rees to ensure his team bikes won’t fall foul of UCI types with clipboards. That is one of the beautiful things about the 3D printing world. You don’t need to be a design whizz to come up with a viable design for the item you want to create. There are thousands of templates for almost anything you can think of (and a lot you probably couldn’t) available to download on open-source sites, and most of them are free.

The angle-checker is not the only tool Rees has made. His repertoire also includes a Shimano crank remover and bearing punches. “I’ve always got the right tool,” he says. “I can design it myself or by looking online – quite often someone else has already done it before, so I contact them and ask them for the file.” The 3D-printing community is friendly in that way, Rees says, with most willing to help each other out. He prints items for other team mechanics who don’t have 3D printers.

Owning a company or working for a UCI team isn’t a prerequisite for entry to the 3D-printing club. Glasgow-based Ryan Fearne heads up component company Ride Stash Components, but for him 3D printing began as a hobby. Having worked in numerous bike shops, Fearne graduated in sports engineering and then worked in medical devices, where he was surrounded, as he puts it, “by lots of toys and 3D printers, high-end sort of stuff”. He subsequently bought his own desktop model to print all manner of bits and bobs, from household items to cycling-related pieces.

(Image credit: Ryan Fearne / RideStash)

Fearne came up with his Ride Stash mount after suffering a mechanical while out riding and realising he needed a decent tool mount. Unable to find what he needed online, he set about designing his own, and the Ride Stash mount was born. Realising he had created an effective product, he decided “we’ll put it on the market” – and it’s proving popular. Fearne prints on UV-resistant ASA plastic in an enclosed printer with filters to prevent harmful fumes. In the early stages, Fearne handed out the mounts to friends, acting on their feedback.

While it seems to have a lot going for it, 3D printing is regarded as dubious by some consumers, according to Fearne. “It’s not good for everything,” he concedes. “I suppose with me it’s trying to show that, you know, you can get some really good quality parts out of it.”

How long, then, before we’re all riding off into the sunset on our 3D-printed bikes? While it’s clearly possible to print a bike, that bank-account-busting swing tag on Tidball’s bike strongly suggests that isn’t the imminent future for most of us. Sturdy sets out the costs of what he does versus the big name bike brands building in traditional ways.”For those companies, the cost of the materials is a few hundred dollars. My material cost is around 50% of what I’m selling the bike for. For me, you’re talking 10 to 12 times what it would cost other companies to produce their bikes,” he explains. “It would take a lot of effort for that approach to work for the industry on a bigger scale.”

It’s more likely that, as 3D printing slowly breaks into the mainstream, with printers and materials becoming more refined and affordable, 3D printing is going to become the go-to option for the average rider looking to create a useful mod for their machine or workshop. “It’s definitely getting towards the mainstream,” says Fearne. “Most people will know someone who’s a bit weird and 3D-prints stuff,” he jokes, “and it’s great to see loads of people picking it up and using it for cycling. If people have a specific problem, they don’t need to go and hunt for the right part, they can have a crack at designing themselves.”

As a mechanic, Rees predicts the 3D printer will have an increasingly valuable role as a workshop sidekick, not just for team staff like himself but in shops too. He gives the example of a previous bike shop he worked for being able to replace a customer’s obsolete fork bushing.

You’re unlikely to find yourself on a 3D-printed bike any time soon. But the chances of your bike ending up with something 3D-printed bolted to it – or perhaps having been adjusted using a 3D printed tool – are increasingly high. That bolt-on might even be something you printed yourself.

CW tried it: ‘Look ye, a printed drip catcher!’

Cycling Weekly web editor Michelle Arthurs-Brennan on her own 3D-printing experiences

Our household’s Creality 3D printer is, in my husband’s words, “the kit car of 3D printers”. It’s fiddly, comes with its own idiosyncrasies, but makes for an enjoyable hobby. It set us back just £120.

Despite both being cyclists, we’ve yet to print anything bike-related. The closest we’ve got to a 3D-printed cycling product has been an ‘Aeropress drip catcher’ – how did we cope without it?! So far, the designs we’ve used have come from open source websites, such as the aptly named ‘Thingiverse.com’. Highlights include the cable organiser we never knew we needed, and the perfect toothbrush holder.

To print bike parts, we would have to upgrade to more expensive, more resilient printing material such as ABS – the downside of which is a toxic particulate risk. We would likely need a more expensive printer too, such as a Bambu, whose printers come with filters to trap toxic particles.

Filippo Ganna’s 3D printed Hour record bike

(Image credit: Getty Images)

At the top level, 3D-printed bikes have been used by Filippo Ganna, Alex Dowsett and Will Tidball, creating quite the buzz around the production method

Pinarello, which developed Ganna’s Bolide with UK-based Metron AE, was very open about its machine. Created in five bonded parts made from a scandium-aluminium-magnesium alloy called scalmalloy, it features shapes impossible to make using carbon-fibre. Ganna used the bike to great effect, knocking the Hour record out of the park with his 55.792km in October 2022.

Dowsett’s team employed 3D printing to create a track-going rear triangle in titanium for his favoured Factor Hanzo time trial bike. He also used Aerocoach 3D-printed handlebar extensions for his 2021 attempt at reclaiming the Hour record, which ultimately fell around 500m short of the mark.

In contrast, Tidball’s bike, developed by the UK Sports Institute (UKSI), is shrouded in secrecy, no doubt partly because it is to be used at this year’s Paris Olympics. Bearing the catchy moniker UKSI-BC-1, the only information on the UKSI website is that the bike is being “built using 3D printing”.

Not all of 3D printing’s cycling-related headlines are positive. The Australian team pursuiters fell foul of a snapped 3D-printed base bar during the qualifying rounds at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. It was removed from sale by manufacturer Bastion immediately afterwards.