Should You Pay Off Your Mortgage?

For those of us who have a home mortgage, paying it off may not be an option. Either you lack sufficient cash, or retiring the mortgage early would leave you cash poor and vulnerable.

Even for those of us who do have the means, the decision whether to pay off the mortgage is unclear. We can come to an approximate answer by comparing the cost of keeping the mortgage to the cost of paying it off, and choose the lesser of the two.

But while the cost of the mortgage is knowable, the cost of paying it off is not. That’s because we cannot know the return we’ll receive by investing the money elsewhere.

Even if the math favors paying off the mortgage, there are a lot of other nuances to consider.

My Dilemma

I bought my house in 2011, financing it with a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage at 3.75% interest. Two years later, lured by an even lower rate environment, I refinanced to a 7-year, adjustable-rate mortgage at just 2.625% interest. This knocked $212 off my monthly mortgage payments, netting me a savings of 18%.

My rationale seemed sound. In addition to saving more than $2,500 a year, refinancing locked me in to guaranteed cheap money for at least 7 years (an eternity, right?).

Moreover, the fine print on the note stipulated that after the 7-year fixed-rate period expired, my rate could adjust up (or down) by no more than 2% per year, and never exceed a maximum of 7.625%.

This number is quite reasonable by historical standards; quite tolerable, too, I reasoned, should it come to pass. After a decade of rock-bottom interest rates—or more accurately the macroeconomic environment holding them down—many predicted rates would never go that high again.

The graph below helps illustrate how one might be forgiven for making this assumption.

Related: What Are the Financial Advantages of Home Ownership?

Related: Renting vs. Buying: The True Cost of Home Ownership

Adjustment Time

In June 2020 the fixed-rate period on my loan expired. My rate went up, but by less than 1% (to 3.5% from 2.625%). This was the first in a series of annual rate adjustments, which were to be calculated by adding 2% to the 1-year LIBOR (since replaced by SOFR) in the quarter preceding the adjustment.

One year later, in 2021, my rate actually went down. For the next 12 months I would pay just 2.5% interest on my mortgage (was that 2013 refi a stroke of genius or what?).

With 12 years of ultra-low rates in the rearview, there was no reason to believe my rate would ever adjust up again.

No Income, No Loan

All the same, I like certainty. So I decided to refi again, this time to a 15-year, fixed-rate mortgage at ~2.5%. Such was the rate being offered in the summer of 2021.

Trouble is, I was a retiree, and 98% of the mortgage lenders out there couldn’t wrap their heads around lending to a zero-income borrower, even if that borrower had more than enough assets to make good on the loan. I submitted one application after another. Each was summarily dismissed.

What of the 2% of lenders that would work with me, those that would make me a so-called asset-only loan? Well, they wanted to charge me a ~1% premium for the privilege.

I punted, reasoning that as long as rates didn’t go up, I could continue to ride the low-interest gravy train, maybe even for the duration of my existing loan. Again, this was an understandable—if not altogether rational—expectation after a decade-plus of ultra-low rates.

Related: Getting a Mortgage When You Have Assets But No Income

The “I” Word

Then came 2022, and we all know what happened next. Inflation reared its head in a big way, and forced the Federal Reserve to raise short-term interest rates, fast and by a lot.

This resulted in two consecutive years of 2% increases on my mortgage (remember, this was the maximum annual increase guaranteed by my lender), pushing my rate up to its current level of 6.5%. Now I’m facing another rate adjustment, to the 7.625% maximum, in June 2024.

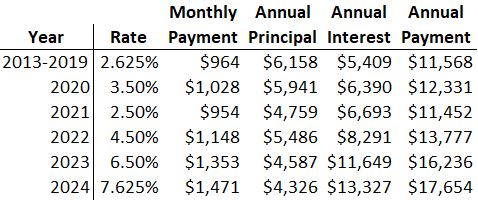

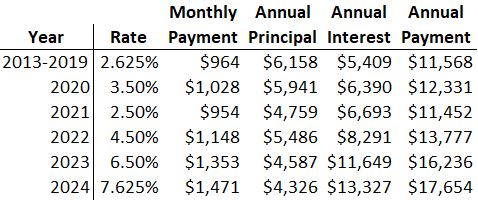

Here’s a table that paints the picture more concretely. It illustrates the effect of moderate rate increases on the actual cost of my mortgage.

For the first 7 years of my loan—the fixed term, lasting from 2013 to 2019—I paid $964 a month on my mortgage. I’m currently paying $1,353 a month and, as of June 2024, I will be paying $1,471. That’s an increase of 53%, which equates to $507 a month ($6,086 a year) more than what I paid during the fixed period of my loan.

What’s more, the higher my rate, the greater the proportion of my monthly payment that goes to interest, not principal. So much for thinking 7.625% would be a tolerable rate.

A Wider View

It’s instructive to note that this is very much the situation facing a lot of businesses in the U.S., and is precisely the pain the Central Bank aims to inflict when it increases the federal funds rate.

The upshot for businesses is that they spend less money. After all, when you’re spending more on debt service, you’re spending less on other things. This cools aggregate demand, thereby bringing the overall price level down (or so goes a half-century of macroeconomic theory).

For businesses, this means less investment in plant and equipment, and maybe even layoffs. For people like me, it means fewer dinners out, and thinking twice about that trip abroad. By hurting businesses and individuals alike in this way, the Fed hopes to wrestle inflation back down to a reasonable level.

Here’s a graph of the Fed’s policy rate dating back to 1970. If you compare it to the one above, graphing the average 30-year mortgage rate over the same period, the correlation is unmistakable.

I try to remind myself that low inflation in the long term is likely worth some pain in the short (but I’m a silver-lining kind of a guy).

Retire the Mortgage?

Why don’t I just pay off the mortgage? Great question! And one to which I have given a lot of thought lately.

Paying off my mortgage would be akin to making a substantial investment in a particular asset class—namely real estate. It would also represent a significant reallocation of my retirement portfolio. At a 7.625% return on investment, I admit it is a tempting prospect.

Consolidation of Risk

But paying off my mortgage has downsides, and not an inconsiderable amount of risk. For one thing, that real estate investment represents a single point of loss.

What if my house burns down? Yes, I’d get money from the insurance company, hopefully enough to rebuild a habitable structure where that smoking hole used to be. But how can I be sure?

Maybe I’d just walk away with that insurance money and become a renter. This would amount to a huge loss on my real estate investment. In this sense, paying off the mortgage seems to me like a dangerous consolidation of risk.

Liquidity Risk

Then there is liquidity risk. Paying off the mortgage would tie up a boat load of otherwise liquid capital I might need for unforeseen circumstances; say a new car if my existing one gives up the ghost.

I’d be forced to sell other assets to generate cash, potentially at a loss.

Related: 3 Bad Financial Decisions That Helped Me Retire Sooner

Tax Implications

Short Term

What about taxes? In order to raise cash to pay off the mortgage, I’d need to sell assets–i.e., stock and bond ETFs and/or mutual funds–in either my brokerage account or my IRA. Either way, this could result in a substantial, one-time tax liability.

And if the sale results in a capital loss? Then I’d have to think hard about selling at a loss assets intended to fund my retirement.

Also, as a recipient of ACA subsidies and cost-sharing reductions, I would lose the majority (if not all) of those benefits in the tax year I sold the assets. I lean heavily into ACA; in fact, without it, I would not have felt comfortable retiring as I did at age 53.

Long Term

The picture brightens a bit when I consider the long-term tax implications of paying off the mortgage.

My retirement income strategy amounts to withdrawing a fixed amount from my brokerage account monthly, and maintaining a cash cushion in that account of about a year’s worth of expenses. In order to maintain that cushion, I sell stock and/or bond ETFs periodically at the long-term capital gains rate.

With the monthly mortgage payment gone, I’d have to sell fewer assets to maintain my cash cushion. This would have the effect of lowering my tax liability in the years after that first-year tax hit.

Interest Rate Risk

What about interest rates? What if they come back down, say by a lot? Then the return on my investment is no longer anywhere near the 7.625% I booked when I paid off the mortgage, and by then it’s too late to do anything about it.

Psychological Implications

The allure of being completely debt-free is powerful. Some might be reading this and think, boy, if only I had the cash to pay off my mortgage, I’d do it in a heartbeat!

You can’t put a price tag on quality sleep. If paying off the mortgage allows you to sleep better at night, the financial costs may be worth it.

Upshot

The decision to pay off a mortgage is not as clear-cut as it may seem. Even if you can afford it, there are myriad factors to consider. Many of these will depend on the particulars of your financial situation. Each must be factored into the equation, and the return assumptions on paying off your mortgage adjusted accordingly.

For my part, I have decided not to pay off my mortgage…at least not yet. I am betting that interest rates will come down sooner than later, thereby reducing my monthly mortgage payments. If/when that happens, I’ll revisit a refi. Conversely, if by 2026 or 2027 I’m still paying 7.625%, then I’ll revisit a payoff.

Mistakes

Some might argue I made a mistake taking an adjustable-rate loan in the first place. I might agree. But that is water under the bridge. There’s nothing I can do about it now, and I’m not going to waste brain cells dwelling on it.

More pertinent (and irksome) to me was giving up so easily on my efforts to refinance in 2021. In hindsight, that 1% premium asset-only lenders were going to charge me looks like a bargain.

I’d be paying ~3.5% on a 15-year fixed-rate loan now, instead of the 6.5% (soon to be 7.625%) I’m paying on my existing loan. Blindly assuming rates would stay low forever was a mistake, and that bad assumption is costing me now.

Part of my decision to punt on the 2021 refi was just plain laziness. I mentioned I like certainty. But I traded the certainty of a fixed-rate mortgage for the convenience of not having to deal with one or more asset-only lenders; notably all the ceremony that accompanies a mortgage refinance–gathering bank and brokerage statements, signing documents, getting appraisals, dealing with third parties, and so on.

Going Forward

Rates may indeed come down again, thereby nudging my mortgage back down to a reasonable level. Even in the best-case scenario, that is not likely to happen any time soon.

The Fed has indicated it intends to cut its policy rate in 2024, perhaps as many as three times. But it takes a long time for the federal funds rate to ripple through to the longer-term rates that affect mortgages.

Silver-lining guy that I am, in the meantime I’ll do my part to tame inflation by spending less money on other stuff.

What Do You Think?

Do you have a mortgage? If so, have you thought about paying it off? What factors did you consider that I didn’t?

Feel free to share your insights in the comments below, so that I and others might learn something from your perspective or experience.

Programming Note

I will be rafting the Colorado River the day this post gets published, which means I won’t be able to read or respond to your comments until after I get back later this month.

Please do not let this discourage you from leaving a comment, however, and/or discussing this topic amongst yourselves.

* * *

Valuable Resources

- The Best Retirement Calculators can help you perform detailed retirement simulations including modeling withdrawal strategies, federal and state income taxes, healthcare expenses, and more. Can I Retire Yet? partners with two of the best.

- Free Travel or Cash Back with credit card rewards and sign up bonuses.

- Monitor Your Investment Portfolio

- Sign up for a free Empower account to gain access to track your asset allocation, investment performance, individual account balances, net worth, cash flow, and investment expenses.

- Our Books

* * *

[I’m David Champion. I retired from a career in software development in March 2019, just shy of my 53rd birthday. To position myself for 40+ years of worry-free retirement, I consumed all manner of early-retirement resources. Notable among these was CanIRetireYet, whose newsletters I have received in my inbox every Monday morning for the last ten years. CanIRetireYet is one of exactly two personal finance newsletters I subscribe to. Why? Because of the practical, no-nonsense advice I find here. I attribute my financial success in no small part to what I have learned from Darrow and Chris. In sharing some of my own observations on the early-retirement journey, I aim to maintain the high standard of value readers of CanIRetireYet have come to expect.]* * *

Disclosure: Can I Retire Yet? has partnered with CardRatings for our coverage of credit card products. Can I Retire Yet? and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers. Some or all of the card offers that appear on the website are from advertisers. Compensation may impact on how and where card products appear on the site. The site does not include all card companies or all available card offers. Other links on this site, like the Amazon, NewRetirement, Pralana, and Personal Capital links are also affiliate links. As an affiliate we earn from qualifying purchases. If you click on one of these links and buy from the affiliated company, then we receive some compensation. The income helps to keep this blog going. Affiliate links do not increase your cost, and we only use them for products or services that we’re familiar with and that we feel may deliver value to you. By contrast, we have limited control over most of the display ads on this site. Though we do attempt to block objectionable content. Buyer beware.

[ad_2]