Shopping for Assisted Living is an Opaque Experience – Center for Retirement Research

[ad_1]

An advocate for improving care and federal oversight in assisted living facilities succinctly described the experience of searching for a safe place for a loved one.

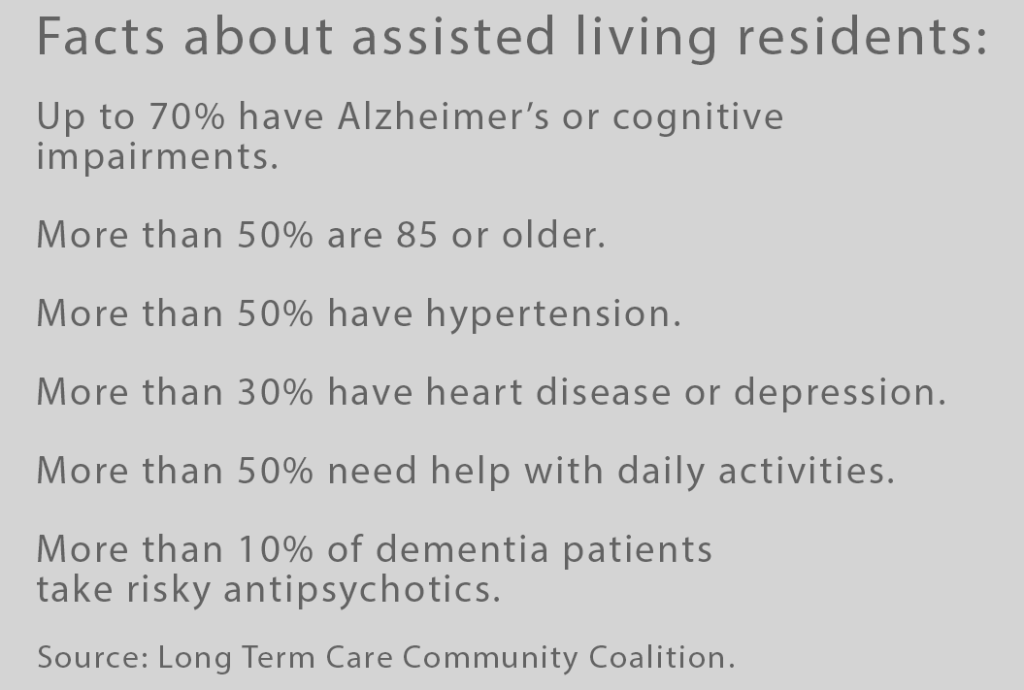

“The assisted living sector operates under a caveat emptor – let the buyer beware – principle,” Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, told the Senate Committee on Aging in January.

His testimony about the lack of transparency in the fastest-growing segment of the long-term care industry provided the context for the discomfiting feeling I had last year when shopping for assisted living for my elderly mother. Mollot’s and other experts’ testimony gave me a better understanding of why I felt that way.

A crucial thing for prospective residents and caregivers to think about is whether a facility can provide the care that’s required now and, even more important, whether it will ramp up to the higher levels of care that inevitably will be needed later. During an initial tour of a facility, administrators provide prospective residents with a list of services or ask about the desired “care package.” But the essential information about what’s important becomes apparent only after the resident moves in. Every parent and spouse has unique needs.

As part of the Senate committee’s fact-finding mission to inform efforts at federal reform to support residents, Chairman Bob Casey, asked Americans to submit their experiences and concerns with assisted living.

Patricia Vessenmeyer told committee members her heartbreaking observations at the assisted living she chose for her husband when she could no longer care for him at home. His Lewy Body dementia introduced a host of complex care issues, both psychological and physical, including fearfulness, combative or sometimes-violent behavior, hallucinations, falling out of bed, and gastrointestinal problems.

As a daily visitor to the facility, the first problem she saw was understaffing in the memory care wing during the day. Nighttime staffing was worse.

The aides who provide the bulk of care are underpaid and turnover is high in these very demanding jobs. Vessenmeyer listed the problems arising from understaffing. The aides helped residents shower only when necessary. Her husband often soiled himself because no one was around to accompany him to the restroom. One time she was the one who intervened to rescue a resident who was lying on the floor while another resident tried to beat him with a cane.

She didn’t see evidence the aides were trained specifically in memory care either. When dementia patients had trouble sleeping, for example, aides would put them in front of a television with the volume turned way up. Television, by stimulating the brain, actually inhibits sleep.

The facility director’s answer to Vessenmeyer’s concerns, she said, was to tell her “to spend less time there and let them do their jobs. I could not abide because they weren’t doing their jobs.”

Judging by her experience, it seems that no amount of investigation and comparison shopping will make clear whether a facility will provide the care that’s needed when it’s needed. Only time and experience will tell.

Jennifer Craft Morgan, a gerontologist at Georgia State University, argued in the hearing that the “crux of the problem” starts with the marketing of the facilities. They “advertise and compete on the basis of amenities, beautiful campuses, luxury food and furnishings, and concierge services.”

This was certainly the case with a couple of the for-profit facilities my mother and I looked at in Florida. One in particular had a landscaped campus, a kind marketing director, a living room with a big, homey fireplace, and high rents for studio apartments. Mom ended up moving into a non-profit in Massachusetts, near my home, that didn’t lean so heavily into lifestyle. I have not encountered any egregious issues. But the care quality it provides as she becomes more frail mentally and physically is an open question.

More federal involvement is a “moral imperative” to protect patients and support families, Mollot told the committee. He and other experts said oversight is appropriate since Medicaid patients in many states qualify for funding for assisted living facilities. States have developed their own standards for monitoring care. But national standards and inspections would provide consistency in care quality and resident safety standards, he said.

Today, “The pervasive lack of transparency,” he said, “extends to virtually every facet of assisted living.”

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us @SquaredAwayBC on X, formerly known as Twitter. To stay current on our blog, join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

[ad_2]