Dialing in crop load data with machine-learning management

[ad_1]

The dream of managing crop load with sensors and smart sprayers moves closer to reality with technological innovation every season.

But it’s a complex dream, with evolving vision systems, new spray technologies and a different way to make crop load management decisions.

“This is a really challenging thing,” said Tory Schmidt of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. He led a session during the precision orchard technology workshop that preceded the International Fruit Tree Association’s annual conference in Yakima in February to highlight the companies in the “rapidly evolving landscape” of drone, tractor and smartphone imaging sensors that promise to track crop load at varying stages from bud to bin.

“We’re not trying to pick winners and losers,” Schmidt said by way of introduction. “If there are things that we can do to help figure out how to get them across the divide from where they are right now to where we all understand they need to be, that will be a great conversation to have.”

During the annual meeting, a panel of growers also spoke about their experiences with these emerging technologies: Gilbert Plath of Washington Fruit and Produce Co., Matt Miles of Allan Bros., and Kristen DeMarree of DeMarree Fruit Farms.

DeMarree’s experience so far involved a lot of trial and error, she said, but that’s how tech companies improve.

“The more input we can give these companies to understand what problems you are facing, the better the companies will become,” she said.

What growers need

Washington Fruit deploys a robust crop load management system involving lots of counting (see “Precision crop load management requires counting, not cameras” ), so Plath was initially excited about the smartphone-based systems.

“We were very hopeful that we’d just be able to tell the counters to go take pictures of the trees,” he said. “We trialed with a handful of those companies, but they did not get to the accuracy levels we required.”

This year, Plath plans to work with vehicle-mounted systems, which would vastly increase the number of trees his company counts.

“We think we count as much as anyone in the industry, and it’s still less than 1 percent of the trees. Vision companies hear that and think they have a home run,” Plath said. “But it’s actually about the marginal value-add to our already robust crop load management system.”

DeMarree said that because her family farms such variable soils, they knew they wanted a full-block scanning system, not a smartphone sampling approach. She worked with Orchard Robotics’ pilot program last season as the company developed its technology.

At the time she needed to make chemical thinning decisions, the company’s fruitlet size distribution data wasn’t accurate enough. But by the time it was hand thinning season, the information was more helpful, she said.

“The challenge is getting scans back in a timely manner. In order to make timely chemical thinning decisions, you need to have the scans back the next day or sooner,” she said. “We’re not 100 percent confident in the accuracy yet, but we see where the systems are going.”

Eventually, she hopes to have tree-specific crop load maps she can connect to her precision sprayer.

Miles wants tree count and trunk diameter data he can use to run cross-sectional area calculations to determine optimum crop load.

Counting every apple on each tree is the more difficult part of that equation because apple trees require leaves and branches, which can block fruit from view. Planar systems allow the camera to see more fruit, but not all.

“Obfuscation is a fancy word for ‘I can’t see it.’ If they can’t see it, they can’t measure it,” Miles said.

It’s how the machine-learning algorithms handle the invisible fruit that matters, he said. With human counting to calibrate, systems should be able to consistently estimate what the imaging misses. He’s wary of approaches that promise to skip that calibration step.

“If you don’t go back and count, how are you going to trust the information you are being given?” he said.

What the sensors can do

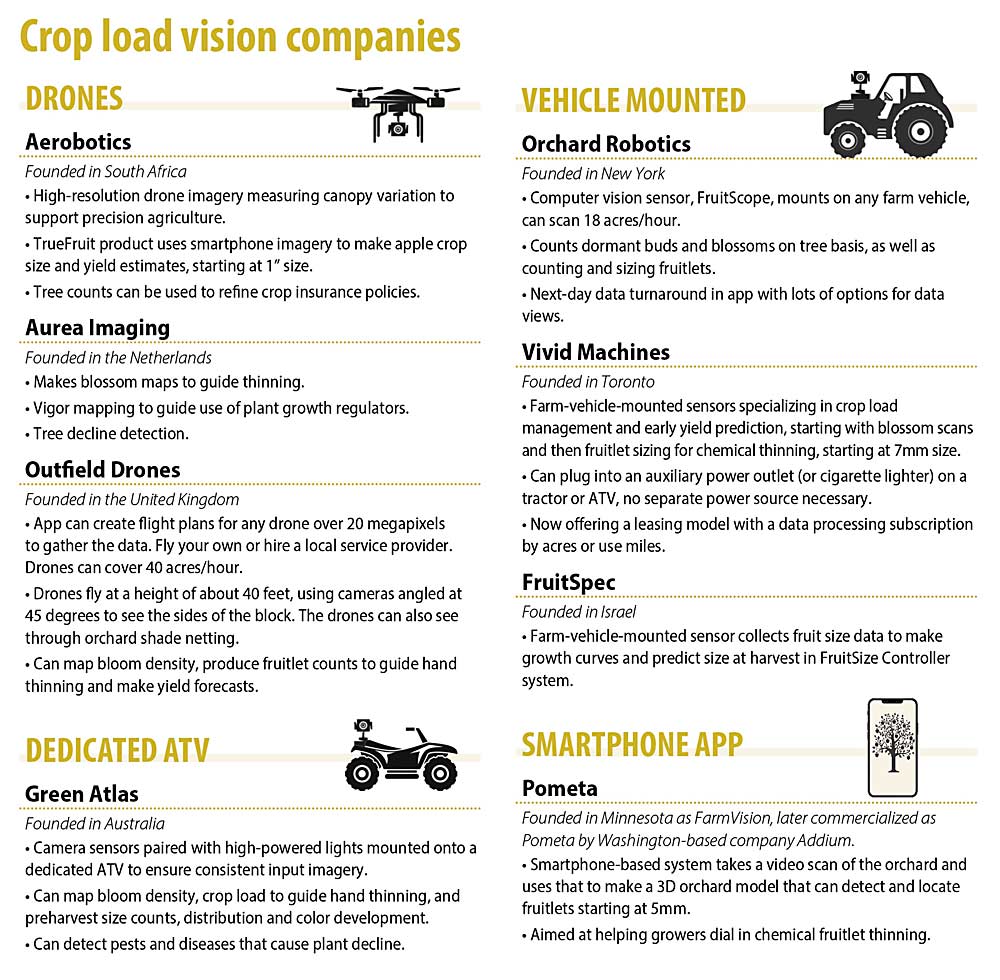

The sensor companies represented at the workshop included Aerobotics, Green Atlas, Outfield Drones, Orchard Robotics and Vivid Machines. Schmidt mentioned a few others that couldn’t attend the conference: Aurea Imaging of the Netherlands, FruitSpec of Israel and Washington-based Pometa.

Some focus more on preharvest yield estimates while others focus on the spring crop load management season.

Two of the drone-based companies, Aerobotics and Outfield, focus on the yield-prediction side of the season, compiling growth curves starting when fruit reaches the size of a golf ball. Tractor-mounted sensors from Vivid Machines and Orchard Robotics aim to guide crop load management decisions with bloom scans and with sizing and counting fruitlets.

“Buds are probably the most difficult,” said Charlie Wu, CEO of Orchard Robotics, a spinoff of Cornell University research.

In the company’s phone app, he showed maps of the crop load, per tree, that could be used to guide how much hand thinning workers need to do.

“We’re trying to make it user-friendly,” he said, adding that most of the tools in the app came from grower suggestions.

Accuracy matters, but so does timing, said Steve Mantle, CEO of innov8.ag, a Washington service provider for Green Atlas’ technology. Orchard timing can be unpredictable, and scanning at full bloom, for example, can be difficult to schedule ahead.

That’s why he is moving away from the service model and believes the sensor technology belongs in growers’ hands, so they can optimize their timing. Vivid Machines is also moving to a lease model for its sensors, as the company scales up this season, said sales rep Spencer Rickel.

Outfield’s model also puts the technology in growers’ hands, said Aaron Tyler, owner of Tyton Aviation, a Washington vendor for the U.K.-based company.

“It will work on any drone over 20 megapixels, so you can fly it yourself or any service provider can do it,” he said. Outfield’s app makes a flight plan for the drone, which can scan about 40 acres an hour.

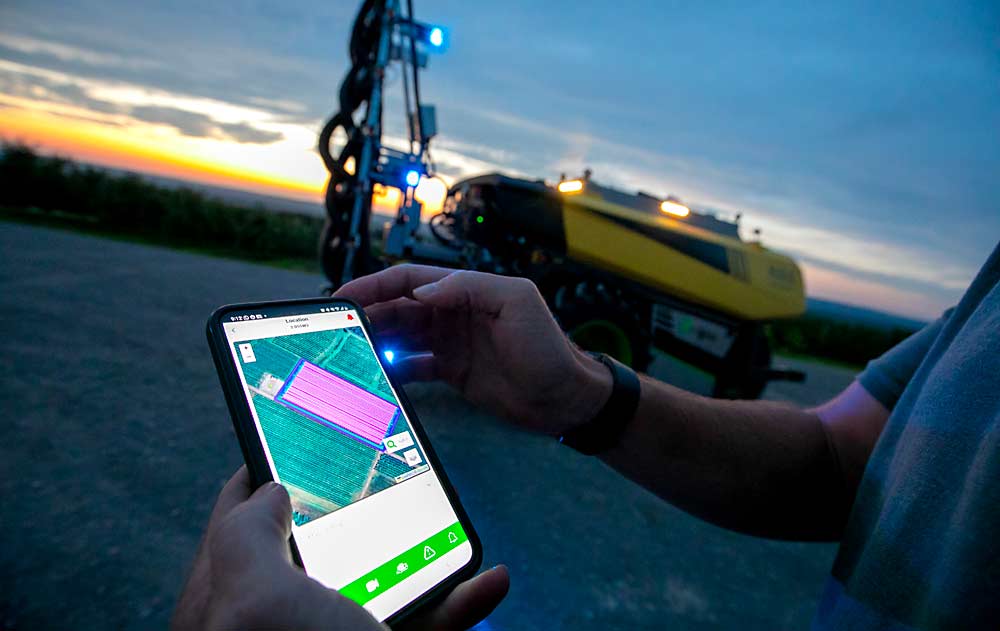

Several of the companies touted their ability to interpret their data into task maps for precision equipment such as the autonomous AgBot developed by Dutch companies AgXeed and Hol Spraying Systems.

Adding smart sprayers to the equation

One invention, pulse-width modulation for sprayer nozzles, opened the door to a wide array of smart spray technologies, said Gwen Hoheisel of Washington State University. Known as PWM for short, the technology allows solenoid valves to change how much product can be sprayed without affecting the pressure that changes the droplet size. The volume control can cycle up to 100 times a second.

“This is 25 years of research coming to fruition,” she said by way of introduction to a separate workshop session on precision sprayers.

Combine that application technology with canopy-size sensors to estimate the leaf area needing coverage and an agronomic interpretation of what to apply, based on that sensor data, and you get precision agriculture, she said.

But smart sprayers, generally, were designed based on canopy sensors. Having them base applications on a GPS map of bloom density collected by a very different sensor is a different ball game.

“It can be done, but it’s not perfect,” she said. “Everybody in the world has been looking at how much spray the canopy can hold. It’s a tiny sector of apples that does three sprays a year for chemical blossom thinning.”

For example, Munckhof Fruit Tech Innovators of the Netherlands developed its PWM-enabled sprayer to reduce crop protection product needs for European growers facing strict regulations. But customers began asking if the same technology could precision-spray each tree based on bloom or fruitlet thinning needs, said Han Smits of Munckhof.

“This is a big step into creating a homogenous orchard with every tree with the same amount of apples,” he said.

Munckhof partnered with a Dutch imaging company, Aurea Imaging, to make maps that give each tree a GPS location and bloom density data. For the sprayer to use that map, it also needs a precise GPS map of the orchard, Smits said.

SmartApply, the most common precision spray technology in Washington, uses lidar canopy sensors for precise, real-time spray volume adjustments, but it isn’t set up to follow that kind of task map, Hoheisel said. A Spanish company, Waatic, makes sensor systems to enable sprayers to do variable-rate application based on input maps.

This season, New Zealand-based Robotics Plus is introducing a new autonomous, hybrid diesel/electric sprayer with PWM that should be able to spray based on task maps, CEO Steve Saunders said.

Michigan Grower Mike Wittenbach, who hosted some Aurea/Munckhof trials, said it’s been a learning curve. He hired a local drone pilot to scan the block at bloom, and Aurea processed the data into a bloom density map. Then he and his team looked at that map to decide how they wanted to spray bloom thinners in the different zones.

It took a lot of calibration for his Munckhof sprayer to be able to follow the GPS-referenced map, but they got to spraying on a tree level last season.

“We have it down to each tree in a 3-by-11 planting,” he said. “The issue is, is it worth your time and does it pay? If you have even bloom, it’s not going to pay. It’s hard for me to put a number on it.”

—by Kate Prengaman