Buy & Hold vs. Fear & Greed

[ad_1]

I was a late bloomer when it came to becoming interested in the markets.

I wasn’t one of these wunderkinds reading Barron’s every weekend and picking stocks when I was young. I knew literally nothing about the financial markets until my senior year in college when I got an internship in sell-side research.

When I got a real job in the industry after graduation I didn’t have any practical investment experience. I had never invested any money outside of a CD at the bank.

Since I had no experience to fall back on the next best thing was to learn from the experiences of others. So I read every investment book I could get my hands on. I studied market history by learning about the booms and busts, from the South Sea Bubble to the Great Depression to the Japanese asset bubble to the 1987 crash to the dot-com bubble and everything in between.

With a better understanding of risk and return, long-term investing made the most sense to me. I worship at the altar of Buffett and Bogle. Buy and hold means taking the good with the bad but the good more than makes up for the bad in the end.

The Great Financial Crisis put these newly formed investment principles to the test.

Stock markets around the globe were down around 60%. The financial system was teetering on the edge of collapse. In the fall of 2008 a hedge fund manager told me on a Friday to get as much cash out of the ATM as I could for fears the banks wouldn’t open the following Monday.

It was a scary time.

Yet here I was, armed with all of this knowledge about the history of market crashes and how they offer wonderful buying opportunities, buying stocks every other week in my 401k and IRA. I almost felt naive when so many people around me were investing from the fetal position.

I kept buying and I never sold. I’ve never really sold any of my stocks beyond the periodic rebalance from one fund or position to the next. And that buy-and-hold strategy has paid off in spades.

Just look at the returns in the 2010s for the S&P 500:

- 2010 +14.8%

- 2011 +2.1%

- 2012 +15.9%

- 2013 +32.2%

- 2014 +13.5%

- 2015 +1.4%

- 2016 +11.8%

- 2017 +21.6%

- 2018 -4.2%

- 2019 +31.2%

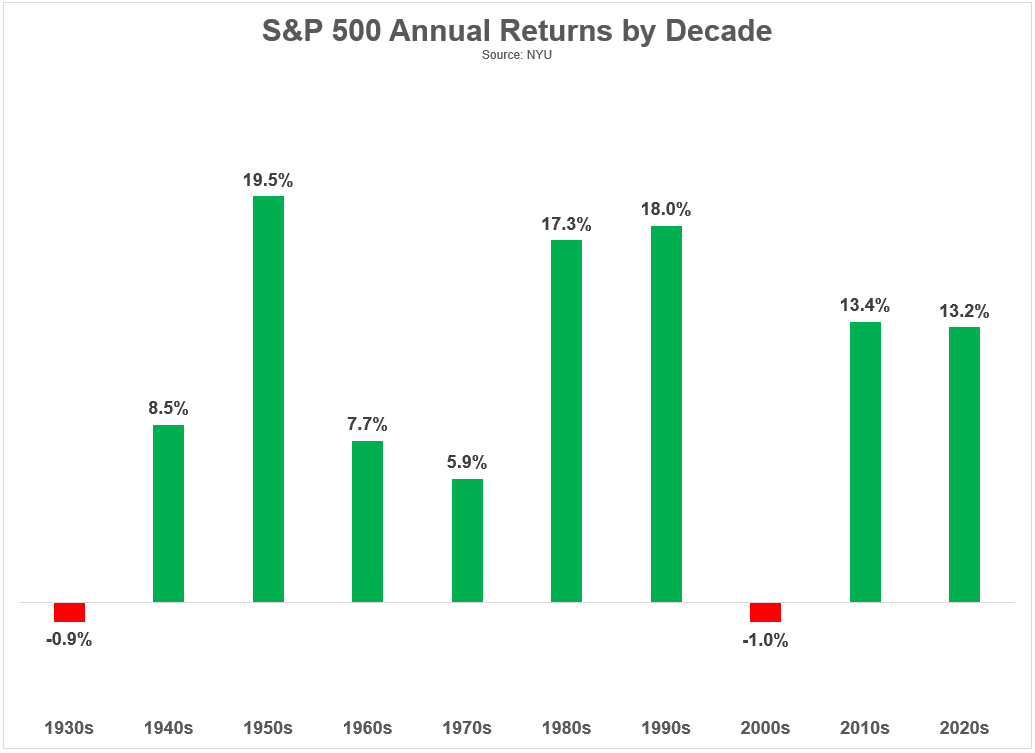

That was good enough for annual gains of 13.4% per year, well above the long-term average.

Things haven’t exactly cooled off in the 2020s either:

- 2020 +18.0%

- 2021 +28.5%

- 2022 -18.0%

- 2023 +26.1%

- 2024 +6.9%

The annual returns this decade (so far) have been 13.3% per year. So we had high returns in the 2010s and they’ve only continued into the 2020s, even with a couple of bear markets.

All of my long-term investing principles have been rewarded over the last 20 years, even when things looked bleak.

Of course, one of the biggest reasons returns have been so stellar is because they were so terrible in the first decade of the century:

- 2000 -9.0%

- 2001 -11.9%

- 2002 -22.0%

- 2003 +28.4%

- 2004 +10.7%

- 2005 +4.8%

- 2006 +15.6%

- 2007 +5.5%

- 2008 -36.6%

- 2009 +25.9%

- 2000-2009 (annualized) -1.0%

But one of the reasons returns were so terrible in the 2000s is because they were so stellar in the 1990s:

- 1990 -3.1%

- 1991 +30.2%

- 1992 +7.5%

- 1993 +10.0%

- 1994 +1.3%

- 1995 +37.2%

- 1996 +22.7%

- 1997 +33.1%

- 1998 +28.3%

- 1999 +20.9%

- 1990-1999 (annualized) +18.1%

We could keep playing this game but I think you get the picture. Here are annual returns by decade going back even further:

The cycle of fear and greed is undefeated. It just doesn’t run on a set schedule.

The excellent returns of the 2010s and 2020s have been wonderful for long-term investors. But it does make me a little nervous because periods of above-average returns are eventually followed by periods of below-average returns.

So what’s the solution?

First off, I’m not going to try to time the market. While above-average returns cannot last forever, they can last longer than you think.

Second, I focused exclusively on large cap U.S. stocks here. Plenty of other areas of the global stock market haven’t done nearly as well. Diversification has not been rewarded this cycle. It will at some point in the future. I don’t know when but diversification is a risk mitigation strategy, not a predict the future solution.

Third, I’m going to keep buying stocks.

I have a lot more money in the market than I did starting out back in 2005 but I’m also saving more money.

It’s always painful when the market falls, but volatility is a friend of the net saver.

I’m a buy and hold investor but that means buying and holding, then buying some more and holding and buying even more and holding that too and so on.

Investing is more fun when the markets are going up.

You just have to prepare yourself for the times they go nowhere or down because that’s part of the long-term too.

Further Reading:

Observations From a Decade in the Investment Business