The loneliness of the indoor trainer. All great business ideas begin with a problem that needs solving. In this case, Eric Min – a tech entrepreneur in his early-40s who had just left behind a tight-knit NYC cycling community to live in London – had both the problem and the solution. “I wanted to get rid of the sense of loneliness that I felt when I rode indoors,” says Min, the originator of what has long been a global super-success, Zwift.

It may come as a surprise to many that Zwift was conceived not in the airy offices of a California tech start-up, or even in New York City, but in London, England. That said, New York certainly inspired what was invented in part to solve a London problem. The original seed was planted for Zwift when Min was living in New York City, training in Central Park with the close-knit cycling community he relied on for regular rides and meet-ups. But then he moved across the pond.

“When I moved to London, for my business, I no longer had that community,” says Min. “I didn’t have a Central Park, and the [London] weather is awful – worse than New York at times. And the roads were just unfriendly. So in order for me to continue training, I had to ride indoors.”

At the time, the only good thing about riding indoors was the potential training gains it could offer. Beyond that, turbo training was synonymous with torturous boredom. As the nights drew in and Min contemplated a dull winter indoors, he would hark back wistfully to the time spent riding with his buddies in Central Park. “I just thought, could we recreate some of this digitally?” Inspired by online gaming, Min decided that the key was community. “We thought, it’s got to be anchored around an experience where you’re around other people.”

New paradigm

(Image credit: Zwift)

The aim, he says, was to recreate in virtual form 80% of what he had experienced in New York – “the community, the competition, the convenience”. Min had, as he puts it, already “sold the vision” by the time he released the initial beta version of Zwift in September 2014, touring the industry with business partner and co-founder of the company Scott Barger.

“The idea was, let’s have a beta, let’s get our early customers to help us come up with a real core product that we can start charging for,” Min explains, adding that take-up was huge: “I think we had 20,000 people interested in joining the beta right there.” He launched the company with Barger, designer Jon Mayfield, whom they’d found on Google, and Min’s old business partner Alarik Myrin, with whom up to that point he’d been building trading platforms for energy markets in London.

One of the first to experience this new paradigm – only the eighth ever, in fact – was New York City coach David Lipscomb. Lipscomb, who is based in Brooklyn and runs the CIS Training Systems coaching company, was invited to try out Zwift’s first ever course – Zwift Island – at a local bike shop and fitting studio. “It was amazing,” says Lipscomb, who saw straightaway the potential of the platform. “I saw immediately,” he says, “how we could use that platform to elevate outdoor riding indoors in a safe environment, which was key.”

The beta riders were able to contest jerseys for fastest lap, KoM and sprint, with the classifications resetting every hour. And Zwift developed fast. Only five months later, even with the platform still in beta, users had covered a million miles on Zwift Island’s little course, and a new world was launched. Watopia, based on a real island in the South Pacific called Te Anou. Watopia remains Zwift’s ‘home’ world and features a mammoth 78 routes. But back then, it featured just one route, a 9.1km loop known these days as the ‘Hilly Route’.

Back then, Zwift’s virtual world could feel rather lonely. Indeed, on a YouTube video replay of the original Zwift Island, luminous and translucent riders in ones, pairs and strings – put in the game to give a sense of community – abound. “Fast forward to now, I think those ghost riders are now Robo pacers,” says Lipscomb, referring to the in-game riders who lead continuous group rides at various watts per kilo. That feeling of riding in company was all part of Min’s original vision of community. “We built the whole business around [the principle that] it’s got to feel like you’re there with other people,” he says.

Zwift in numbers

Number of Zwift worlds: 12

Number of Zwift courses: 129

Subscription fee: $14.99 / £12.99

Annual revenue: $103m (2023)*

Number of users: 4 million

Peak Zwift: 46,375 users (2021)

Longest course: 173km (The Full PRL in London, taking in 11 ascents of Box Hill – aka ‘Fox Hill’ in Zwift)

Shortest course: 1.9km (Bell Lap in Crit City)

* Source: Latka SaaS database

Not in the plan

That community is one of Zwift’s strongest selling points these days, but it is also famed for competition, from club time trials to elite road race leagues – it’s all here. The first competitive events on the platform were actually nothing to do with Zwift – they were just one element of the community-led developments that immediately started to spring up and which continue to be instrumental for the platform. “What we noticed – and this is something that was not in our plan – was that the community started to organise themselves, to build tools; they built websites, spreadsheets… tools we didn’t have.”

There were spreadsheets to organise events and to verify performance; tools to help with set-up problems. “A lot of these are still in the wild,” Min says.

One of them was Zwift Power, which was so instrumental in collating event results that Zwift ended up acquiring it. “We had to help scale it because there were hundreds of thousands of users on it,” Min explains.

Zwift began to expand rapidly from the very start, first adding Watopia and then its first real-life world – Richmond – ahead of the US city hosting the road World Championship in September 2015, even before the finished-product launch. Innsbruck was added for the 2018 Worlds and then Yorkshire a year later. Even at that time, though, there were plenty of cyclists for whom a group ride on a virtual platform represented the antithesis of what cycling in company was supposed to be about. But then came Covid.

Peak Zwift

(Image credit: Jenna Norman)

Suddenly, the idea of sharing real-life space with other people huffing and puffing their way through a ride became unappealing and even illegal. That was when many found virtual cycling. “That was a real push,” says Kate Veronneau, director of women’s strategy at Zwift. “Definitely during Covid, a lot of people, even the real naysayers, didn’t really have a choice at times [but to use Zwift].” According to Zwift Insider, ‘Peak Zwift’ – the most users on the platform at any one time – was 46,375, achieved in 2021.

Veronneau had joined Zwift in 2016, recruited to run the Zwift Academy talent ID competition, which was designed to find hidden talent on the platform and recruit riders to the WorldTour. It has run every year since, and has proved far more worthy than a bit of fun publicity, with 2020 winner Jay Vine having won the Tour Down Under and two stages of the 2022 Vuelta a España.

During the Covid lockdowns, it wasn’t just your average rider in the street who found themselves surprise converts to virtual cycling. “I love the story of [AG Insurance-Soudal rider] Ash Moolman Pasio,” says Veronneau. “At the beginning of Covid, she very begrudgingly started training indoors, and after a month went back outside and broke her time up Rocacorba by three minutes, and was just hooked. [Zwift] literally unlocked the potential of a pro,” she says.

As well as an estimated doubling of its users, lockdown was a major accelerant for a series of events that elevated Zwift to another level – beginning with hosting a virtual Tour de France and ending as the title sponsor and key driver in the biggest race on the women’s calendar, the Tour de France Femmes Avec Zwift.

The virtual Tour de France was held over three weekends in July 2020, as the pros geared up to restart the WorldTour. Men and women tackled six stages each, run on Watopia and the brand new France world including, rather charmingly, a recreation of the finale of the real-life Tour, taking in the Champs-Elysées and the Place de Concorde. Exciting racing in the Virtual Tour proved the catalyst for making a long-awaited women’s Tour de France a reality.

“I think that helped spur the conversation of, ‘Alright, I think it’s time – we could do this together,” Veronneau says of ASO and Zwift. “ASO knew they needed to have a women’s race soon, but they also needed somebody to come on board and push them over the edge,” opines Veronneau. “So I think us signing on as a five-year title sponsor – four years with an option for five – was something that needed to really make it happen.”

“Lockdown left us no alternative”

Among the many Zwift lockdown converts was elite time triallist and road racer Alice Lethbridge. A member of Kingston Wheelers and holder of time trial competition records at 100 miles and 12 hours, Lethbridge and numerous club-mates had retained a robust suspicion of virtual riding until it became the only option.

“I didn’t really like the idea because, to me, group riding was sort of about being outside with people,” Lethbridge says. “But in lockdown when we couldn’t be riding with friends it was sort of the only option. And then I think people realised how good it was.” Lethbridge was quickly hooked. So hooked, in fact, that she ended up setting a new virtual Everesting record on the platform of nine hours 27 minutes, riding repeats of Alpe du Zwift. It was part of a club fundraiser for a local hospital and hadn’t actually been part of the plan when she began the ride.

“My coach at the time didn’t really want me to do it,” says the 39-year-old, “but the club started tweeting that I’d do another ascent if they hit a fundraising target, so I had to keep going!” Hard as it was, it didn’t put Lethbridge off indoor cycling and she continues to do much of her training on Zwift and is active in the community, as part of a women’s think tank and helping to run women’s teams.

Bumps in the road

(Image credit: Zwift)

Despite the fact that Zwift remains the market-leading virtual cycling platform, it has not had an entirely smooth ride. There were moans about the significant subscription hike from £7.99 to £12.99 ($10-14.99 in the US) in 2017 – though, to be fair, that price has remained unchanged ever since. More problematic for the company in recent years has been the post-Covid downturn.

Post-lockdowns, uptake tailed off considerably as life returned to normal. In May 2022, Zwift was forced to cancel plans for a new smartbike, owing to what it termed the “current macroeconomic environment”. Then, early last year, the company laid off 15% of its workforce – 80 people – and just a fortnight ago it laid off more staff, and co-CEO Kurt Biedler, who had only been in the job a year, resigned.

“Growth has not rebounded at a fast enough pace to justify all of the investments that we have been making,” was how Zwift explained the latest round of redundancies. “As a result, we are taking action to become leaner with a continued focus on delivering great experiences for our community.”

Another bugbear for Zwift – one that exists across all of virtual cycling in fact – is the ever-present spectre of ‘weight doping’, with riders able to make potentially race-winning alterations to their own watts per kilo simply by altering the weight they self-declare. At high-level races with prize money at stake, riders will usually need to verify their vital statistics using a video protocol and their equipment must also strictly adhere to guidelines. For last year’s UCI esports World Championship, all riders used the same Tacx Neo 2T trainer, to level the playing field as far as possible.

Despite ongoing tough times, Zwift remains at the top of the virtual cycling tree, thanks in large part to the huge community it built up – just as Min had intended – by being first to make it big on the indoor scene. For Veronneau, connecting women and growing the global female community remains paramount. She is convinced there are many more women out there whom Zwift has not yet reached, while Min revealed that he hoped to be able to give cycling clubs the tools to recreate their own jerseys on Zwift.

Want to ask the founder about where the platform is headed? You’ll find Min on Zwift most days, probably riding Sugar Cookie – “one of my favourite courses because it’s mostly flat” – while pondering exactly that question.

The rivals: who are Zwift’s main challengers?

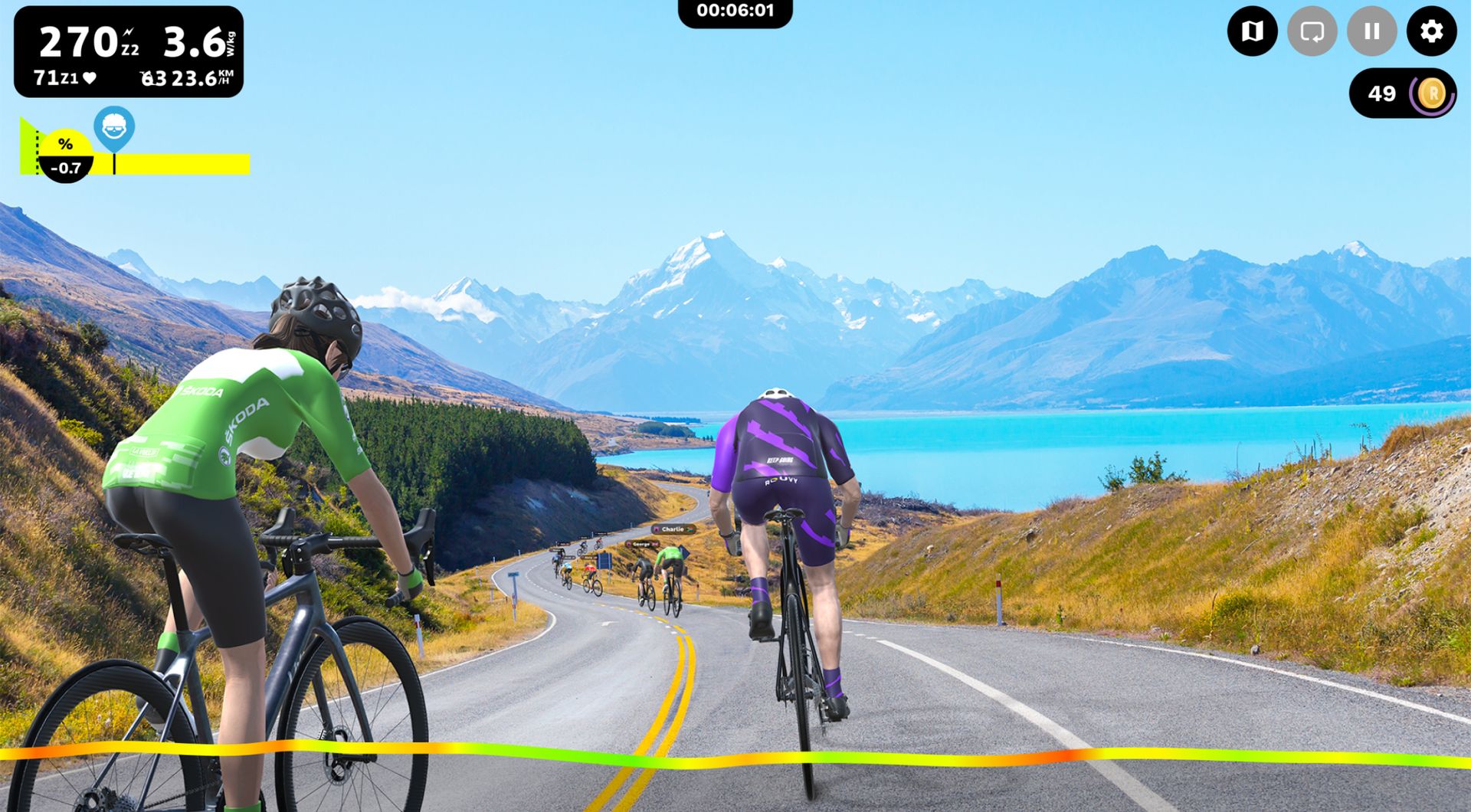

Riders in Rouvy’s realistic landscape

(Image credit: Rouvy)

While Zwift may have been the first major virtual cycling success, it is not the only platform to forge a digital path out of indoor training boredom. In fact, anyone looking to take up virtual riding right now is spoiled for choice, with a number of Zwift alternatives available, with their own USPs.

Bkool, for example, allows users to ride three different indoor velodromes, while Rouvy, which was founded even before Zwift, uses real-life scenery as part of its ‘augmented reality’ model. Peloton, which focuses on online spin classes, has had a bumpy ride since a major lockdown upturn but remains a popular player with indoor cyclists, as does TrainerRoad.

The platform that has had possibly the biggest direct impact on Zwift in recent times is MyWhoosh. The UAE-based company was founded in 2019 and has enjoyed some very useful exposure as a partner of the UAE men’s and women’s WorldTour cycling teams – with one of its claims being that it is Tadej Pogačar’s virtual platform of choice.

Most cuttingly for Zwift, last August MyWhoosh was granted the UCI esports World Championships for 2024-26, ousting Zwift as the host. “Naturally we’re very disappointed,” Zwift said in a statement at the time. But it insisted its commitment to racing at all levels remained unchanged and added: “We will continue to innovate and drive this new sport forward.”