Chest fairings can give riders a “significant” aerodynamic advantage and decide time trials, a new study has discovered.

The research, published in the Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, found that a large chest fairing could result in time gains of almost a second per kilometre.

Even the most discrete of fairings could offer a few seconds’ advantage over a course, which “could very well decide who wins and who loses the race”, concluded engineering researchers Bert Blocken, Fabio Malizia and Thijs van Druenen of Heriot-Watt University, KU Leuven and TU Eindhoven.

A fairing is any object added to the bike or rider designed solely to improve aerodynamics and reduce drag.

More recently, riders have turned to adding objects into their skinsuit to alter the shape of their body, helping to smooth the passage of air around it. Triathletes have been known to put water bottles down their jerseys to optimise their frontal area, while in cycling, riders like Andy Schleck, Dan Bigham and Jonas Vingegaard have used smaller fairings in time trials, the latter appearing to do so at last year’s Tour de France.

UCI guidelines stipulate that “any non-essential element or device” may not “modify the morphology of the rider”; however, teams have tried to circumvent this rule by placing race radios as chest fairings, a practice which is not permitted.

In the new study, the researchers took a mannequin of a male rider, 177cm in height, and ran time trial simulations inside a wind tunnel in Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

They found that fairings can give rise to “significant drag aero reductions”, with wider objects yielding the largest gains.

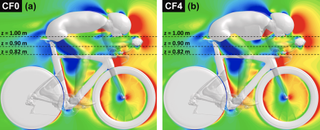

Diagrams showing static pressure on a rider without (left) and with a large fairing (right).

(Image credit: Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics)

At speeds of around 55km/h, for example, riders can save up to 0.78 seconds per kilometre, with gains even larger at slower speeds, up to 0.9 seconds at 46.8km/h. “[This] might be perceived as counter-intuitive,” the researchers noted. “The reason is that at a lower speed, more time is needed to travel a km, hence also the drag benefit – that is a fixed percentage of drag area and a fixed percentage of cycling speed, irrespective of the total riding speed – can be exploited for a longer duration for this km.”

At this year’s Tour de France, the peloton will tackle two individual time trials, the first coming on stage seven, 25km in length and counting 300m elevation. The researchers calculated that, at an average speed of 46.8km/h, riders with large fairings could gain a whopping 22.4 seconds over their rivals.

“For a cycling discipline in which sometimes tenths or exceptionally even thousands of a second can be decisive, the use of a chest fairing, even a very small one, could very well decide who wins and who loses the race,” they said.

The researchers noted, however, that their study did not consider the impact of head, tail or cross winds. They also conceded that savings will differ based on a rider’s size and positioning.

On-body fairings became a hot topic in the UK time trialling scene last season, prompting discussions of a clampdown within Cycling Time Trials (CTT), the governing body.

Aero expert Dr Xavier Disley told Cycling Weekly that he believes they “shouldn’t be allowed”.

“If you turn up to a bike race and the guy next to you is dressed up like a transformer, are you going to feel like you’re in the right place?” he said.

In the second half of 2023, the researchers shared the findings of their study with the UCI, who subsequently reiterated their ban on fairings.