[ad_1]

- Noam Elyashiv takes materials as she finds them and alters them only slightly but with poetic specificity

- Long worktables held jewelry laid out in discursive pairs mixed with fragments and drawings

- Pin stems were epic plot points

- The reviewer became intensely aware how nearness fuels the experience of jewelry

Workspace

September 21–October 14, 2023

Chazan Gallery at Wheeler, Providence, RI, US

As I leaned in to examine the details of a brooch, I watched the light arc over its surface in response to my approach and disappear as I withdrew, like a private sunrise. This is the revelatory opportunity of the close looking demanded by the jewelry of Noam Elyashiv. Her exhibition Workspace, at the Chazan Gallery, in Providence, made me intensely aware of how nearness fuels the experience of jewelry. To be near is to be intimately adjacent and yet still retain some level of separation. As philosopher Byung-Chul Han explains, “nearness is negative in that remoteness is inscribed within it.”[i] In that narrow space between things lies incredible tension, and in that gap the tiniest of gestures becomes epic. This is precisely the space Elyashiv’s jewelry asks us to inhabit.

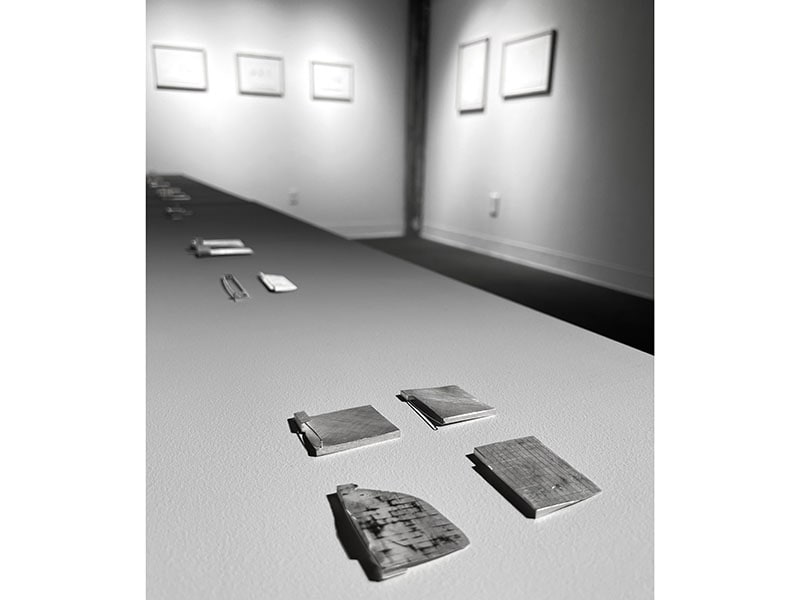

The exhibition’s long worktables hold jewelry laid out in discursive pairs mixed with fragments and drawings, giving the feeling that processes are underway. Objects spanning 30 years of making in a dazzling array of media appear to be in the act of unfolding, rather than coming to rest. These are verbs, not nouns, or—as Elyashiv told me as we walked through the show on an October afternoon—”not jewelry, not art, but work.”

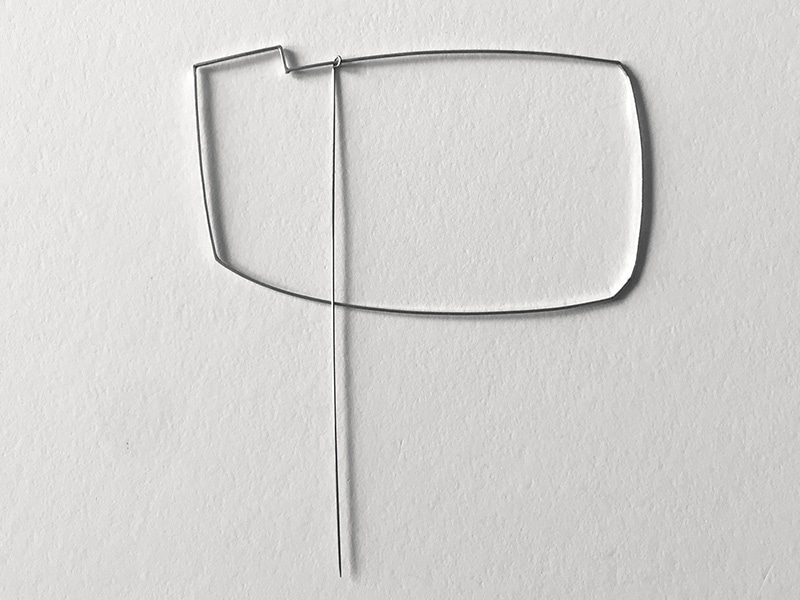

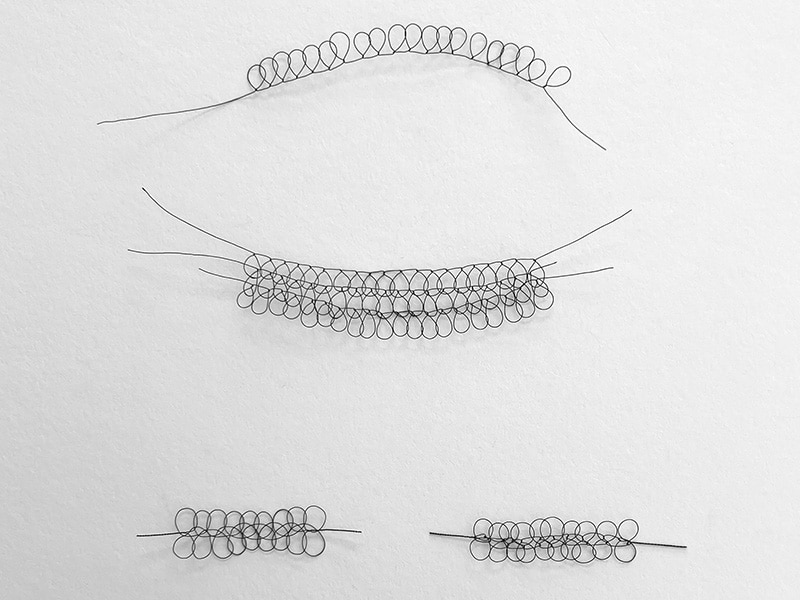

Each table contained a world of inquiry. The first we looked at, titled “Sketchbook,” comprised a series of wire studies in which delicate lines spiral in on themselves, wrapping endlessly inward. Some are flower-like in appearance and others evoke a kind of tender algebra. Their fragile inward twisting demonstrates an intense amount of calculation, control, and care. Made from incredibly fine binding wire, the fragments appear vulnerable yet strong as they frame loops of space. Any binding was only onto themselves. As Elyashiv explained, “I had the vocabulary of line and nothingness. Growing from nothing is everything.” Elyashiv, who grew up near the Negev Desert, understands what it is to exist in vastness and to see the hard-fought miracle of becoming amid the acute lens of space.

Other works directly speak to the materials of jewelry, from the perspective of a skillful hand and historian. A table titled “Not Forever” included a bracelet that replaced the form of pearls with flat circles of milky-white fine silver, the pearls’ perfect spheres of nacre translated into subtly overlapping discs of metal. Precision and mathematics manifest her close attention, while material transformation elicits the narrative tension of difference. On the same table was a set of brooches inspired by the breastplate worn by the ancient High Priests, as described in the Book of Exodus, in the Bible. The pinky-sized stones described in the text are exchanged for drips of enamel in one, and their names stamped into silver in the other: “…opal. jasper. emerald…” This exegesis upends what we expect to find in jewelry, while ironically existing exactly as one would read the names of the gemstones in the Bible: as language.

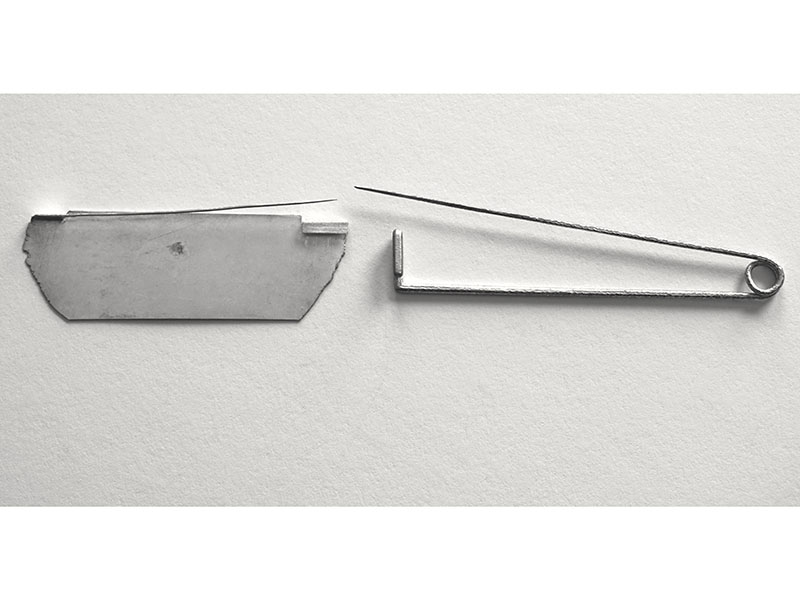

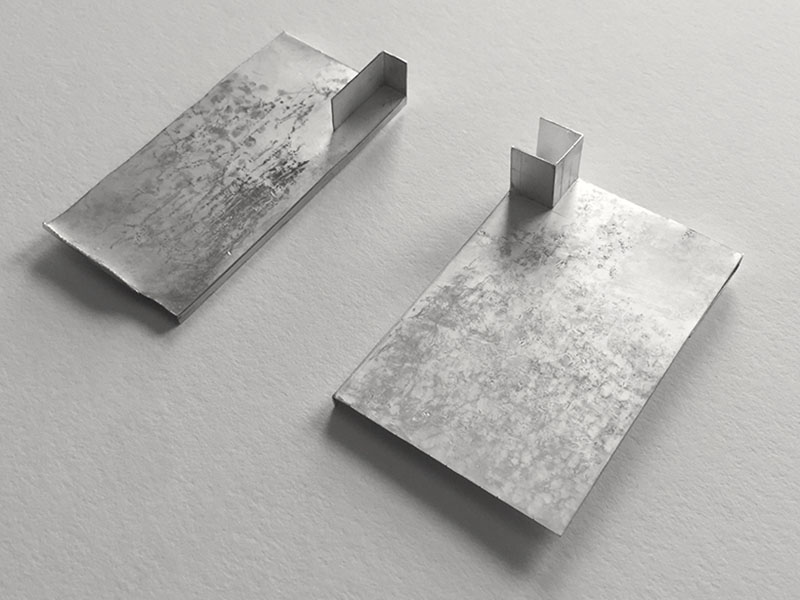

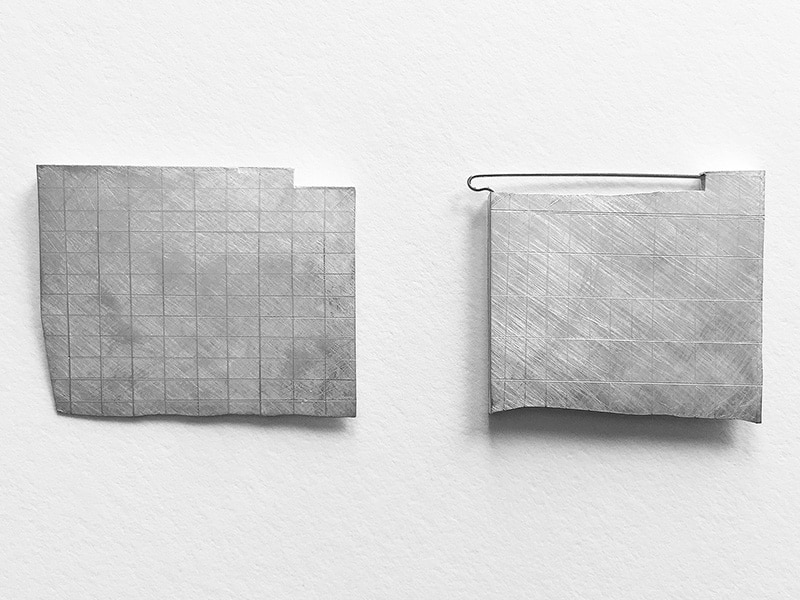

Deep negotiations with materials manifest a respect for autonomy set against a willingness to engage. If in nearness we come close, but allow the other to retain an independent self, here we revel in the tension of their meeting. Throughout the show Elyashiv takes materials as she finds them—a scrap of silver, a funnel, a handful of ribbon—and alters them only slightly but with poetic specificity. One of the newer collections, Backs & Fronts in Dialogue, consists of 21 brooches laid out in pairs. Elyashiv selected fragments of silver and, using a self-imposed set of rules, made the subtlest of adjustments—scoring a single fold, burnishing an edge, forging a pin stem.

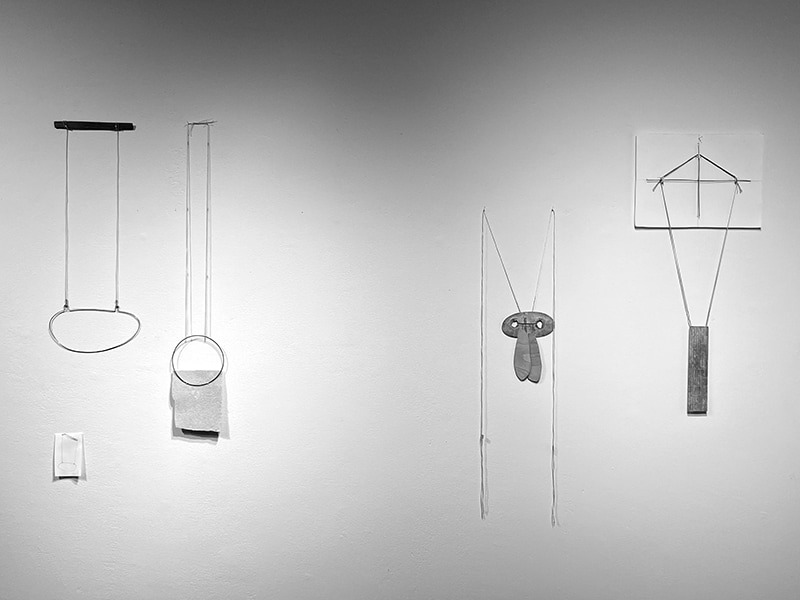

In fact, pin stems become epic plot points throughout the exhibition. Many of the brooches on display are turned so that we see what would typically be perceived as the back. This reveals a poignant jewelry moment, in the gesture of pinning, as we bind an object onto ourselves. She shows us a pervasive hierarchy that doesn’t have to exist: We typically prioritize that which we show others, rather than that which faces only ourselves. Equality is of utmost importance to Elyashiv and she shows us how it exists in our relationship with matter, revealing formal prejudices so closely held we didn’t realize we carried them.

Nearby, a set of transparent wax objects, palm-sized, are meditations in mathematics and masterworks of engineering. Each grouping of two to three objects shares a similarity. They occupy the same amount of surface area or share the same weight, but each has been folded in subtly unique proportions. At first they seem like doubles until their differences slowly emerge through careful observation. Their heft is in these differences. Without a pin stem, and in such a vulnerable material, their function is not wearability or permanence, but conception and production like the performance of a mathematical magic trick. This is maker and material in conversation, pushing the other to see the limits of their relationship.

Throughout the exhibition, these relationships are lovingly tested in ways that feel ongoing. Whether wearable jewelry or fragment, Elyashiv’s work radiates an aura of completeness. As we were leaving, she pointed out some seams that she’d never welded closed and told me, “you have to know when it’s enough.”

Reviews are the opinions of the author alone, and do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[i] Byung-Chul Han, The Agony of Eros (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017) 13.

[ad_2]